The median polish basics

The median polish is an exploratory technique used to extract effects from a two-way table. As such, a median polish can be thought of as a robust version of a two-way ANOVA–the goal being to characterize the role each factor has in contributing towards the expected value. It does so by iteratively extracting the effects associated with the row and column factors via medians.

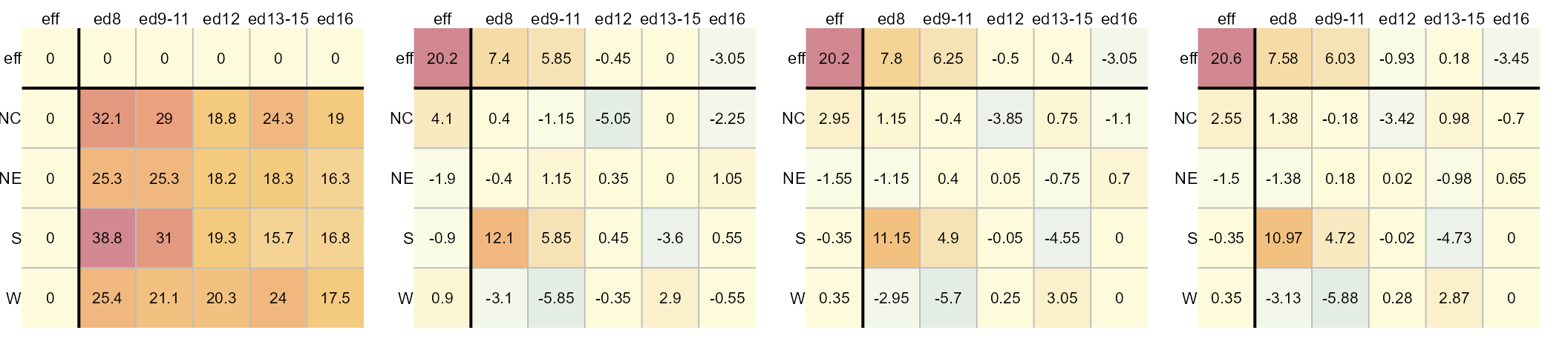

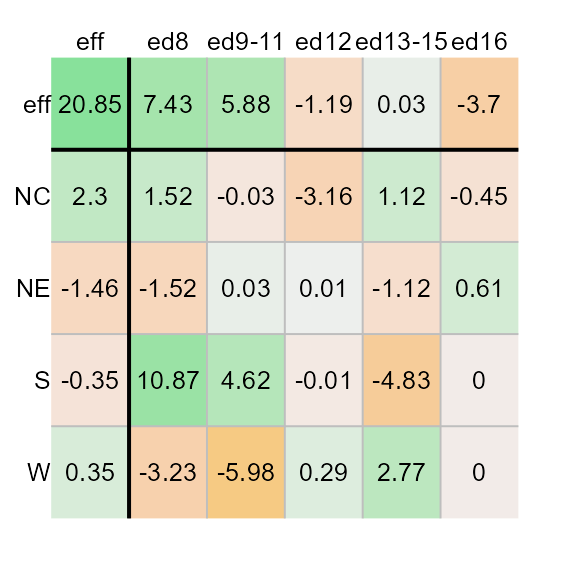

For example, given a two-way table where 1964 through 1966 infant

mortality rates1 (reported as count per 1000 live births) is

computed for each combination of geographic region (NE,

NC, S, W) and each level of the

father’s educational attainment (ed8, ed9-11,

ed12, ed13-15, ed16), the median

polish will first extract the overall median value, then it will

smooth out the residual rates by first extracting the median

values along each column (thus contributing to the column factor), then

by smoothing out the remaining residual rates by extracting the

median values along each row (thus contributing to the row factor). The

smoothing operation is iterated until the residuals stabilize. An

example of the workflow is highlighted in the following figure.

The left-most table is the original data showing death rates. The second table shows the outcome of the first round of polishing (including the initial overall median value of 20.2). The third and forth table show the second and third iterations of the smoothing operations. Additional iterations are not deemed necessary given that little more can be extracted from the residuals. For a detailed step-by-step explanation of the workflow see here.

The resulting model is additive in the form of:

\[ y_{ij} = \mu + \alpha_{i} + \beta_{j} +\epsilon_{ij} \] where \(y_{ij}\) is the response variable for row \(i\) and column \(j\), \(\mu\) is the overall typical value (hereafter referred to as the common value), \(\alpha_{i}\) is the row effect, \(\beta_{j}\) is the column effect and \(\epsilon_{ij}\) is the residual or value left over after all effects are taken into account.

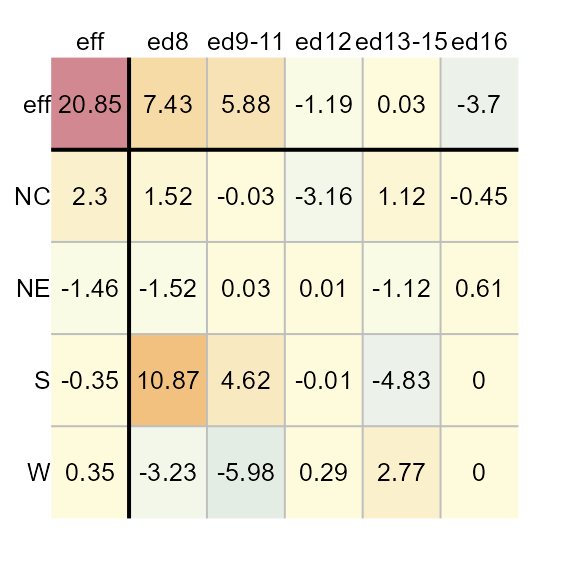

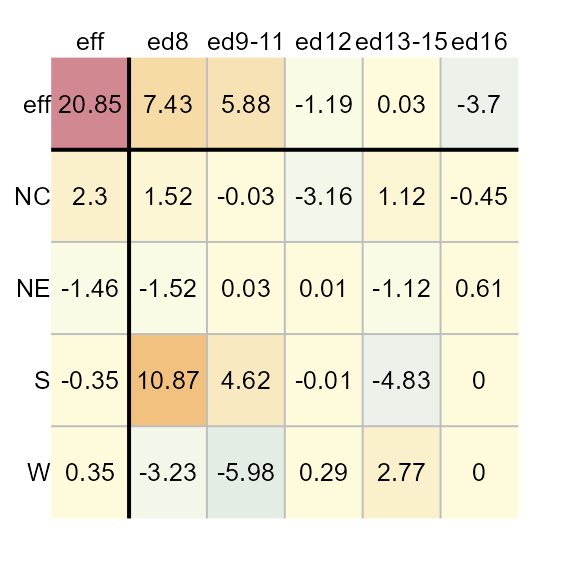

Each factor’s levels are displayed in the top row and left-most

column. In the above example, the region is assigned to the rows and the

father’s educational attainment is assigned to the columns. The father’s

educational attainment can explain about 11 units of

variability (7.58 - (-3.45)) in death rates vs

4 units of variability for the region (2.55 -

(-1.5)). As such, the father’s educational attainment is a

larger contributor to the expected infant mortality than the regional

effect.

Implementing the median polish

This package’s eda_polish is an augmented version of the

built-in medpolish available via the stats

package. A key difference is that eda_polish takes the

input dataset in long form as opposed to medpolish which

takes the dataset in the form of a matrix. For example, the infant

mortality dataset needs to consist of at least three columns: one for

each variable (the two factors and the expected value).

head(inf_mort)

region edu perc

1 NE ed8 25.3

2 NE ed9to11 25.3

3 NE ed12 18.2

4 NE ed13to15 18.3

5 NE ed16 16.3

6 NC ed8 32.1The median polish can then be executed as follows:

The function will output the table as a plot along with a list of

components that are stored in the M1 object. If you want to

suppress the plot, you can set the parameter

plot = FALSE.

The M1 object is of class eda_polish. You

can extract the common values, and the row and column effects as

follows:

M1$col

edu effect

1 ed8 7.43125

2 ed9to11 5.88125

3 ed12 -1.19375

4 ed13to15 0.03125

5 ed16 -3.70000Ordering rows and columns by effect values

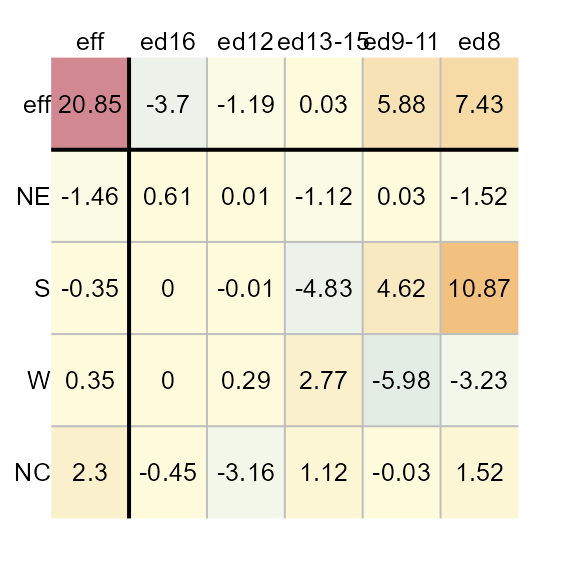

To order the row and column effects by effect values, set the

sort parameter to TRUE.

M1 <- eda_pol(inf_mort, row = region, col = edu, val = perc, sort = TRUE)

Applying a transformation to the data

You can have the function re-express the values prior to performing

the polish. For example, to log transform the data, pass the value

0 to p.

M1 <- eda_pol(inf_mort, row = region, col = edu, val = perc, p = 0)

If you are re-expressing the data using a negative power, you have

the choice of adopting a Tukey transformation

(tukey = TRUE) or a Box-Cox transformation

(tukey = FALSE). For example, to apply a power

transformation of -0.1 using a Box-Cox transformation, type:

M1 <- eda_pol(inf_mort, row = region, col = edu, val = perc, p = -0.1, tukey = FALSE)

Defining the statistic

By default, the polishing routine adopts the median statistic. You

can adopt any other statistic via the stat parameter. For

example, to apply a mean polish, type:

M1 <- eda_pol(inf_mort, row = region, col = edu, val = perc, stat = mean)

The eda_polish plot method

The list object created by the eda_pol function is of

class eda_polish. As such, there is a plot method created

for that class. The plot method will either output the original polished

table (plot = "residuals"), the diagnostic plot

(plot = "diagnostic"), or the CV values

(cv).

Plot the median polish table

You can generate the plot table from the median polish model as follows:

Adjusting color schemes

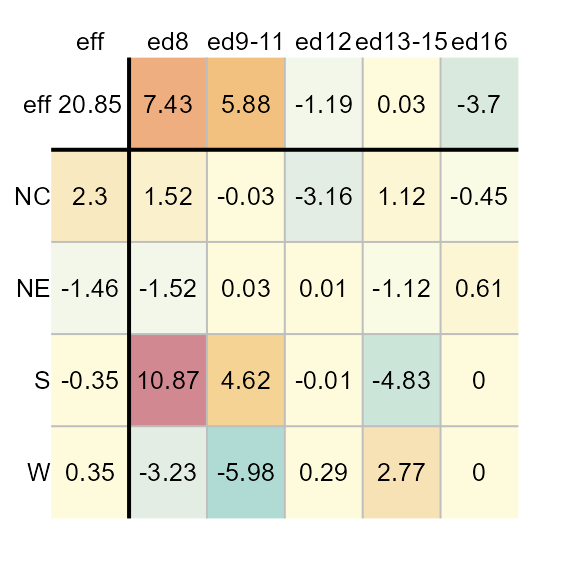

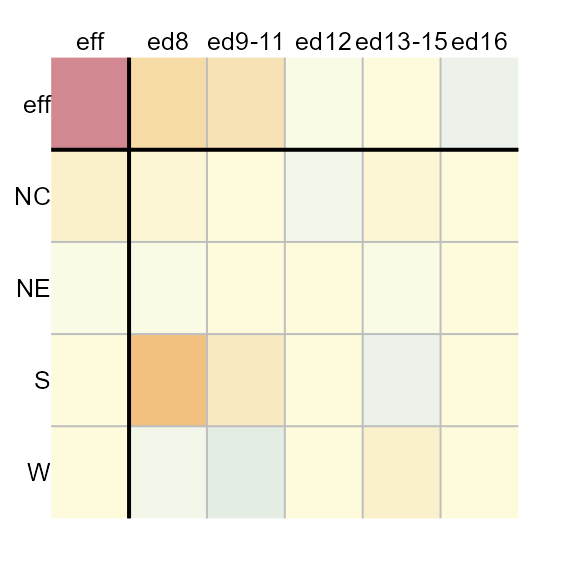

Excluding common effect from the color palette range

By default, the range of color palettes are defined by the range of

all values in the table–this includes the common effect value.

To prevent the common value from affecting the distribution of color

palettes, set col.com to FALSE.

plot(M1, col.com = FALSE)

Note how the distribution of colors is maximized to help improve our view of the effects. This view makes it clear that the father’s educational attainment has a greater effect than the region.

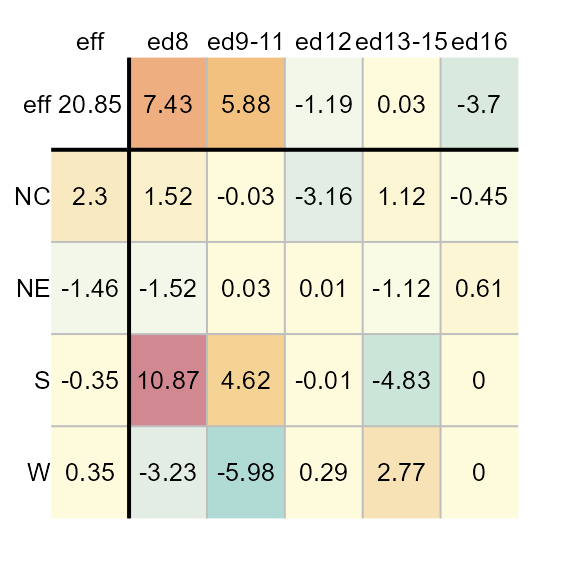

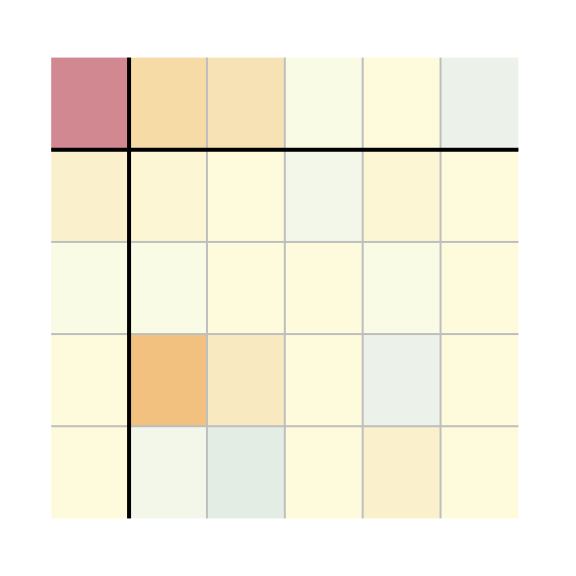

Excluding row/column effects from the color palette range

If you want the plot to focus on the residuals by maximizing the

range of colors to fit the range of residual values, set

col.eff = FALSE.

plot(M1, col.eff = FALSE)

Note that setting col.eff to FALSE does not

prevent the effects cells from being colored. It simply ensures that the

range of colors are maximized to match the full range of residual

values. Any effect value that falls within the residual range will be

assigned a color.

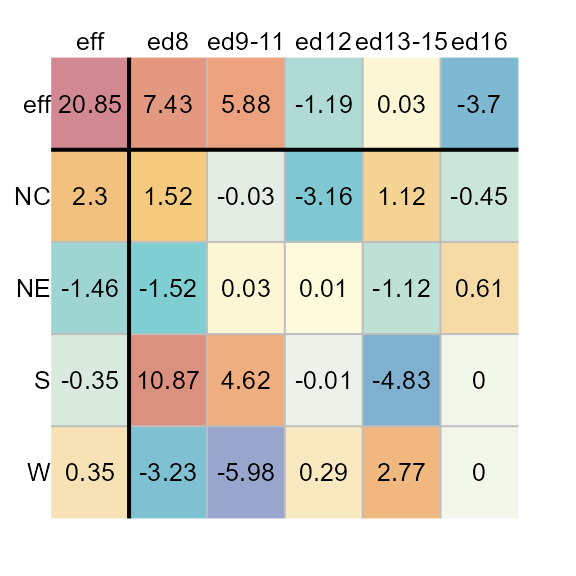

Changing color schemes

By default, the color scheme is symmetrical (divergent) and centered

on 0. It adopts R’s (version 4.1 and above) built-in

"RdYlBu" color palette. You can assign different built-in

color palettes via the colpal parameter.

You can list available colors in R via the hcl.pals()

function.

If you want to limit the output to divergent color palettes, type:

hcl.pals(type = "diverging")

[1] "Blue-Red" "Blue-Red 2" "Blue-Red 3" "Red-Green"

[5] "Purple-Green" "Purple-Brown" "Green-Brown" "Blue-Yellow 2"

[9] "Blue-Yellow 3" "Green-Orange" "Cyan-Magenta" "Tropic"

[13] "Broc" "Cork" "Vik" "Berlin"

[17] "Lisbon" "Tofino"For example, we can assign the "Green-Brown" color

palette as follows. (We’ll remove the common effect value from the range

of input values to maximize the displayed set of colors).

plot(M1, colpal = "Green-Brown", col.com = FALSE)

The default color scheme is symmetrical and linear, centered on

0. If you want to maximize the use of colors, regardless of

the range of values, you can set col.quant to

TRUE which will adopt a quantile color scheme.

plot(M1, col.quant = TRUE)

You’ll note that regardless of the asymmetrical distribution of

values about 0, each cell is assigned a unique color

swatch.

When adopting a quantile color classification scheme, you might want to adopt a color palette that generates fewer unique hues and more variation in lightness values. For example,

plot(M1, col.quant = TRUE, colpal = "Green-Orange")

Adjusting text

You can omit all labeled values from the output by setting

res.txt to FALSE.

plot(M1, res.txt = FALSE)

Likewise you can omit all axes labels by setting

label.txt to FALSE. This may prove useful when

applying a median polish to a large grid file.

plot(M1, res.txt = FALSE, label.txt = FALSE)

You can adjust the text size via the res.size,

row.size and col.size parameters for the

numeric values, the row names, and the column names respectively. For

example, to set their sizes to 60% of their default value, type:

plot(M1, row.size = 0.6, col.size = 0.6 , res.size = 0.6)

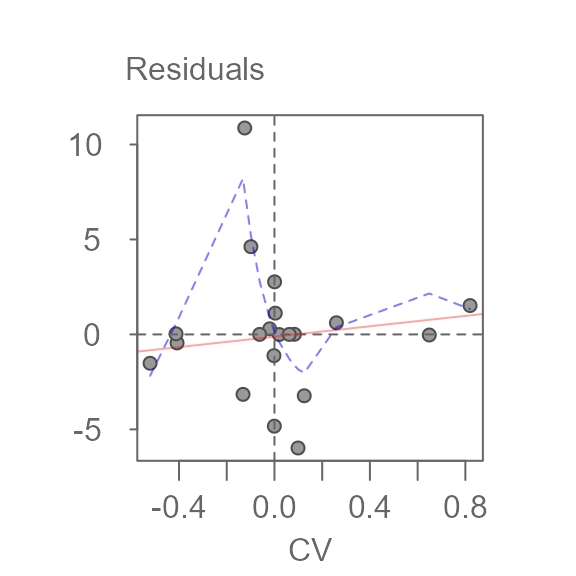

Exploring diagnostic plots

The plot method will also generate a plot of the

residuals vs comparison values (CV), herein referred to as the

diagnostic plot.

plot(M1, plot = "diagnostic")

A bisquare robust line is fitted to the data (light red line) along with a robust loess fit (dashed blue line). The function will also output the line’s slope. This slope can be used to help estimate a transformation of the data, if needed.

To generate your own plot, simply extract the cv

component from the M1 list. The cv component

is a dataframe that stores the residuals (first column) and CV values

(fourth column). The first few records of the dataframe are shown

here:

head(M1$cv)

NULLThe diagnostic plot helps identify any interactions between both effects. If interaction is suspected, then the model is no longer a simple additive model; The model needs to be augmented with an interactive component of the form:

\[ y_{ij} = \mu + \alpha_{i} + \beta_{j} + kCV +\epsilon_{ij} \]

where \(CV\) = \(\alpha_{i}\beta_{j}/\mu\) and \(k\) is a constant that can be estimated from the slope generated in the diagnostic plot.

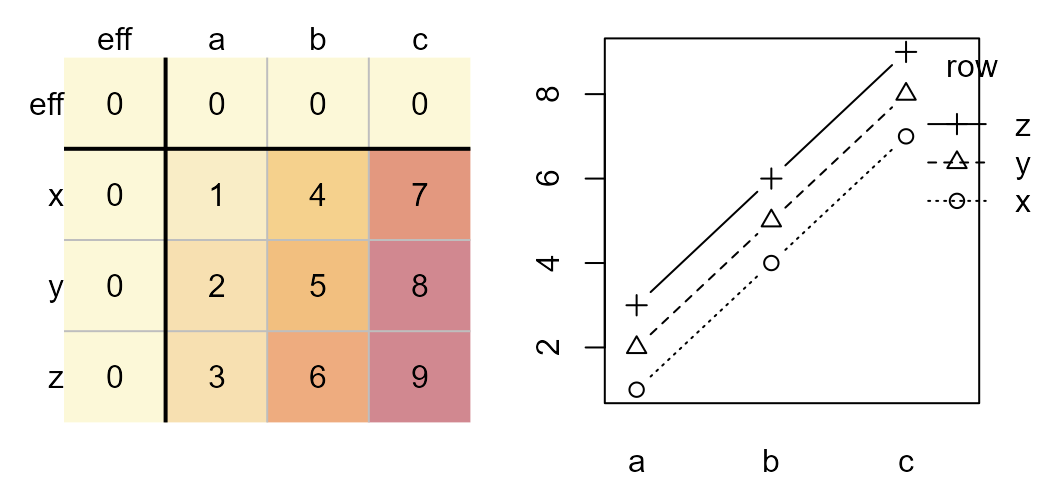

A truly additive model is one where the changes in the response

variable from one level to another level remain constant. For example,

given the bottom-left matrix of initial response values, changes in the

response variable from level a to level b are

constant regardless of the row effect. For example, going from

a to b at level z elicits a

change in response of 6 - 3 = 3. This is the same observed

change in values from a to b at levels

x and y (4-1 and 5-2

respectively). At all three row levels, the change in expected values

from a to b is the same–an increase of

3 units. Likewise, changes in response values between rows

x and y or y and z

are constant (1) across all levels of the column effect.

The additive effect can be observed in an interaction plot as shown on

the right. The column effect is plotted along the x-axis, the row effect

is mapped to each line segment.

Original dataset (left). Interaction plot (right).

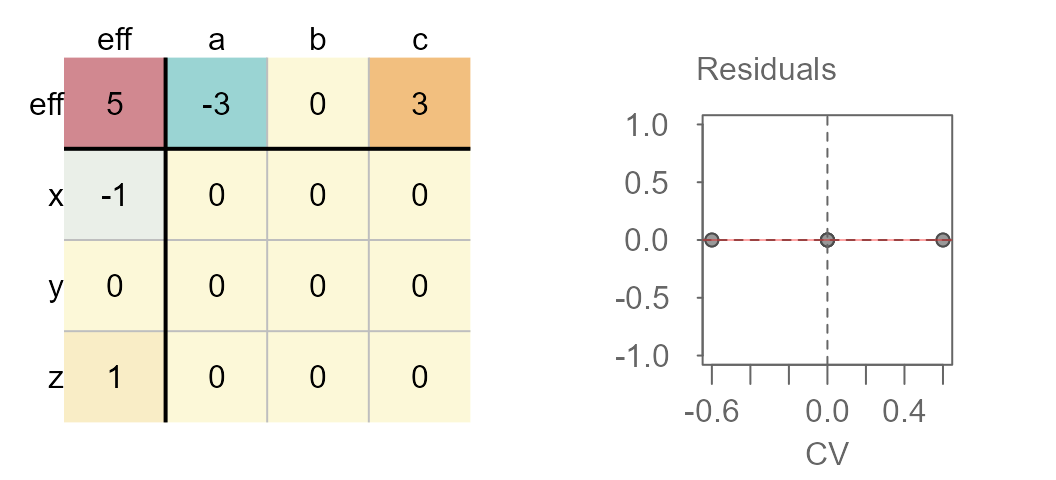

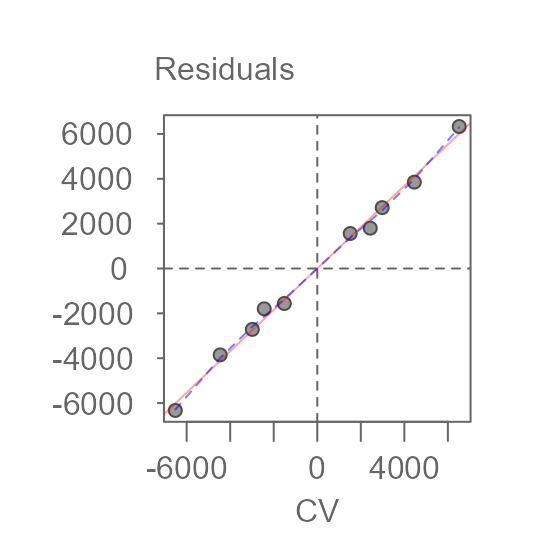

Parallel lines indicate no interaction between the effects. A median polish generates the following table and diagnostic plot:

Median polished data showing no interaction between effects

You’ll note the lack of pattern (other than a flat one) in the accompanying diagnostic plot.

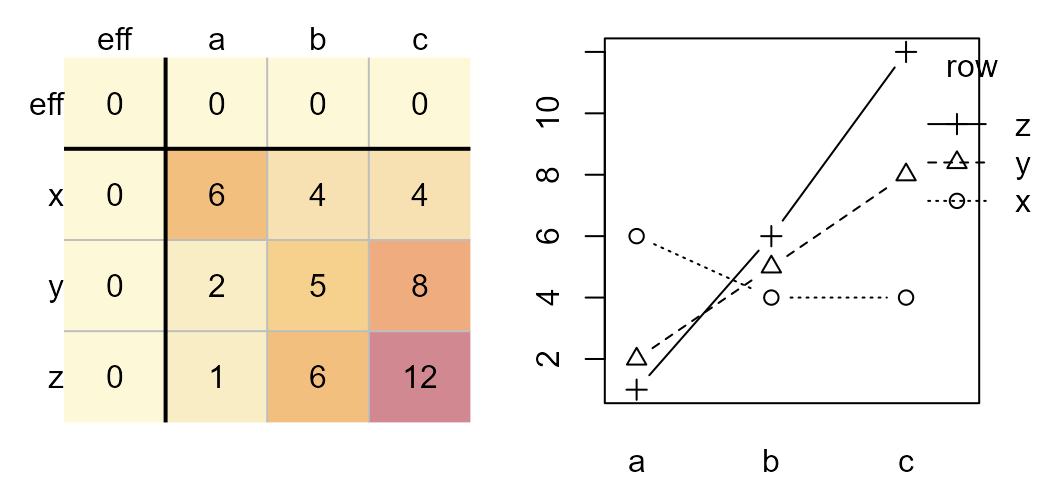

Now, let’s see what happens when an interaction is in fact present in the two way table.

Original dataset (left). Interaction plot (right).

Note how the lines are no longer parallel to one another in the interaction plot. Now let’s run the median polish and generate the diagnostic plot.

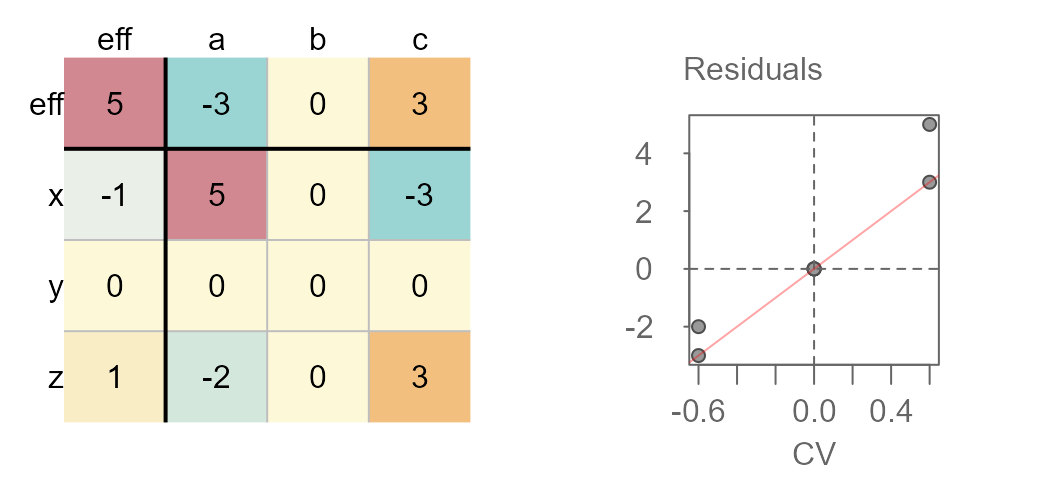

Median polished data showing interaction between effects

You’ll note the upward trend in residuals with increasing comparison values. This is usually a good indication of interaction in the effects. Another telltale sign is the pattern observed in the residuals of the median polish plot with low residuals and high residuals in opposing corners of the table.

If an interaction is observed, you should either include the interaction term in the additive model, or you should seek a re-expression that might help alleviate any interaction between the effects.

If you choose to include the interaction term in your model, the coefficient \(k\) can be extracted from the slope generated in the diagnostic plot.

If you choose to re-express the data in the hopes of removing any interaction in the data, you can try using a power transformation equal to \(1 - slope\) (slope being derived from the diagnostic plot).

The infant mortality dataset used in this exercise does not suggest interaction between effects in the diagnostic plot. Next, we’ll look at another dataset that may exhibit interaction between its effects.

Another example: Earnings by sex for 2021

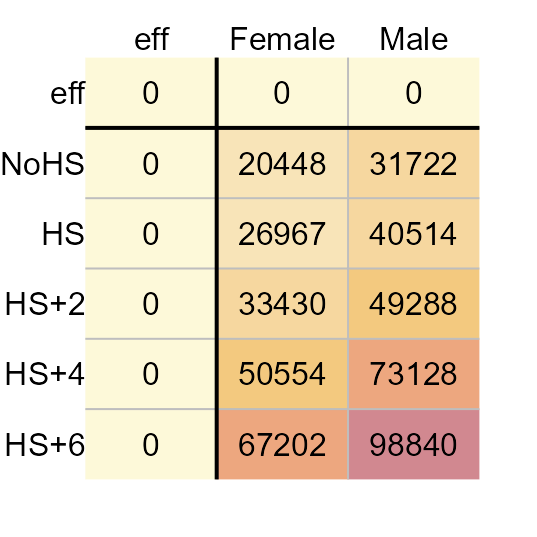

The dataset consists of earnings by sex and levels of educational attainment for 2021 (src: US Census Bureau).

# edu <- c("NoHS", "HS", "HS+2", "HS+4", "HS+6")

# income <- data.frame(Education = factor(rep(edu,2), levels = edu),

# Sex = c(rep("Male", 5), rep("Female",5)),

# Earnings = c(31722, 40514, 49288, 73128,98840,20448,

# 26967, 33430, 50554, 67202))

income

Education Sex Earnings

1 NoHS Male 31722

2 HS Male 40514

3 HS+2 Male 49288

4 HS+4 Male 73128

5 HS+6 Male 98840

6 NoHS Female 20448

7 HS Female 26967

8 HS+2 Female 33430

9 HS+4 Female 50554

10 HS+6 Female 67202The Education levels are defined as follows:

-

NoHS: Less than High School Graduate -

HS: High School Graduate (Includes Equivalency) -

AD: Some College or Associate’s Degree -

Grad: Bachelor’s Degree

The original table (prior to running the median polish), can be

viewed by setting maxiter to 0 in the call to

eda_pol.

eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings , maxiter = 0)

2021 Average earnings for the US.

Next, we’ll run the median polish.

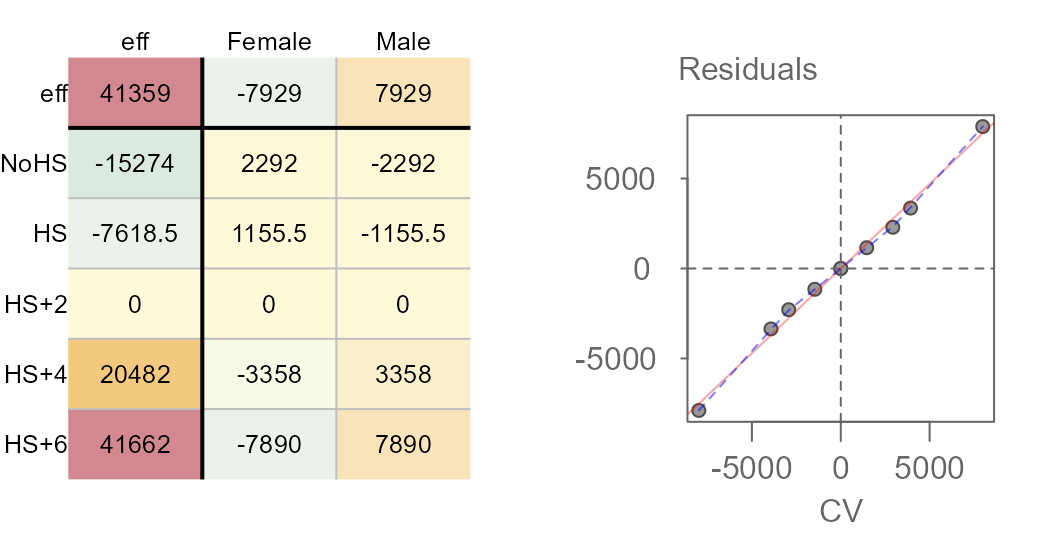

M2 <- eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings , plot = FALSE)Next, we plot the final table and the diagnostic plot.

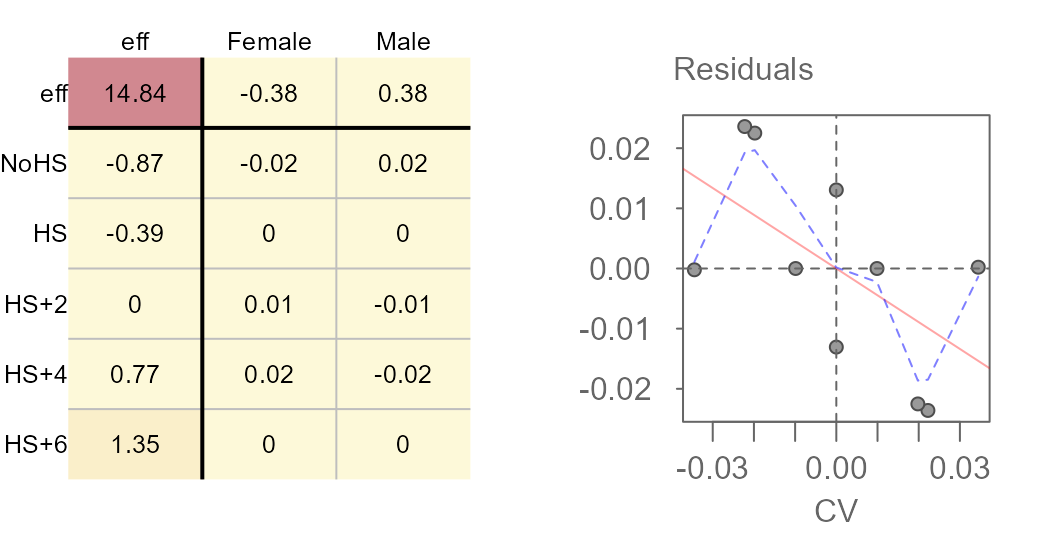

Here’s what we can glean from the output:

- Overall, the median earnings is $41,359

- Variability in earnings due to different levels in education attainment covers a range of $56,936 while that for different sexes covers a range of $15,858.

- Some of the residuals are quite large suggesting that there may be much of the variability in earnings that may not be explained by the row and column effects. The residuals explain $78,392 of the variability in the data.

- The diagnostic plot suggests a strong interaction between the sex effect and the education effect. This implies, as an example, that differences in earnings between sexes depend on the level of educational attainment.

- The slope between residuals and CV values is around 0.94.

Given strong evidence of interaction between the effects, we need to take one of two actions: We can either add the comparison values (CV) to the row-plus-column model, or we can see if re-expressing the earnings values eliminates the dependence between effects.

Adding CV to the row-plus-column model

The CV values are computed and stored in the median polish object.

They can be extracted from the model via the M2$cv

component or they can be visualized via the plot function.

The following figure shows both the original residuals table (left) and

the CV table (right).

plot(M2, res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

plot(M2, "cv", res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

Median polish residuals (left) and CV values (right).

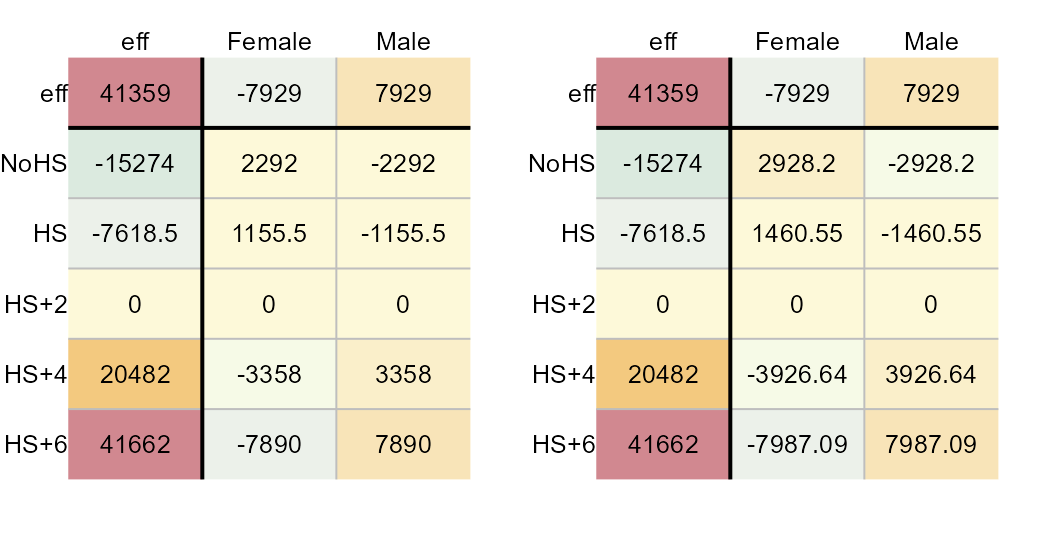

If the comparison value is to be added to the model, we will need to

compute a new set of residuals. These residuals can be plotted by

setting add.cv to TRUE and by specifying a

value for k. Using the slope to estimate k we

get:

plot(M2, "cv", res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

plot(M2, "residuals", add.cv=TRUE, k = 0.94,

res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

CV values (left) and new set of residuals (right).

These two tables provide us with all the parameters that are needed to construct the model. For example, the Female-NoHS earnings value can be recreated from the above table as follows:

\[ Earnings_{Female-NoHS} = \mu + Sex_{Female} + Education_{NoHS} + kCV_{Female-NoHS} + \epsilon_{Female-NoHS} \] Where:

- \(CV_{Female-NoHS} = \frac{(Sex_{Female})(Education_{NoHS})}{\mu}\)

- \(k\) is a constant that can be estimated from the diagnostic plot’s slope (0.94 in this example).

This gives us:

\[ Earnings_{Female-NoHS} = 41359 -7929 -15274 + (0.94)(2928.2) -460.5 \]

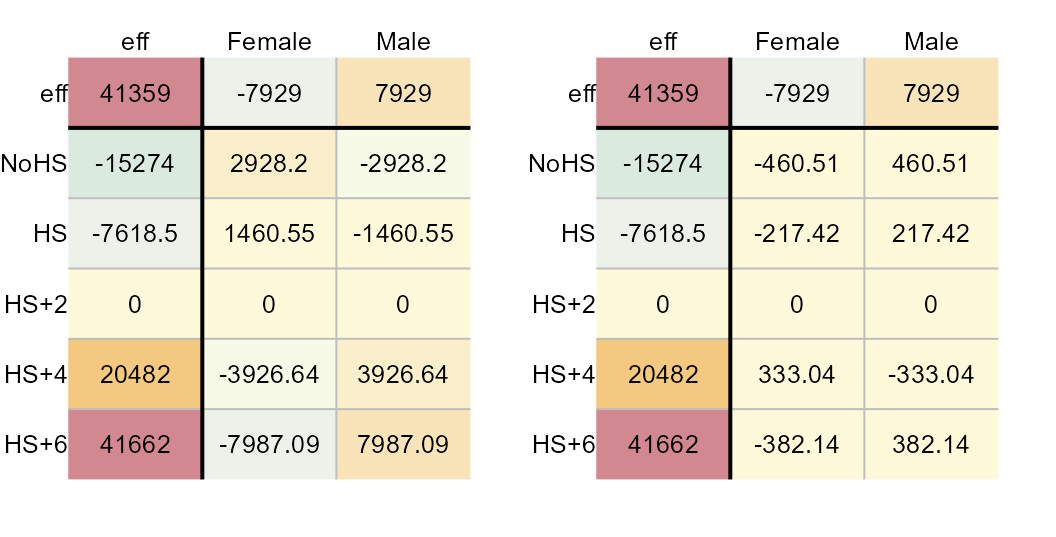

Re-expressing earnings

It’s possible that the earnings as presented to us are in a scale not

best suited for the analysis. Subtracting the slope value (derived from

the diagnostic plot) from the value of 1 offers a suggested

transformation that may provide us with a scale of measure best suited

for the data. We’ll rerun the median polish using a power transformation

of 1 - 0.94 = 0.06.

M3 <- eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings ,

plot = FALSE, p = 0.06)Next, we plot the final table and the diagnostic plot.

Median polish output (left) and CV values (right).

The power of 0.06 may have been a bit too aggressive given that we’ve gone from a positive relationship between CV and residual to a negative relationship between the two. Tweaking the power parameter may be recommended. This can be done via trial and error, or it can be done using a technique described next.

Fine tuning a re-expression

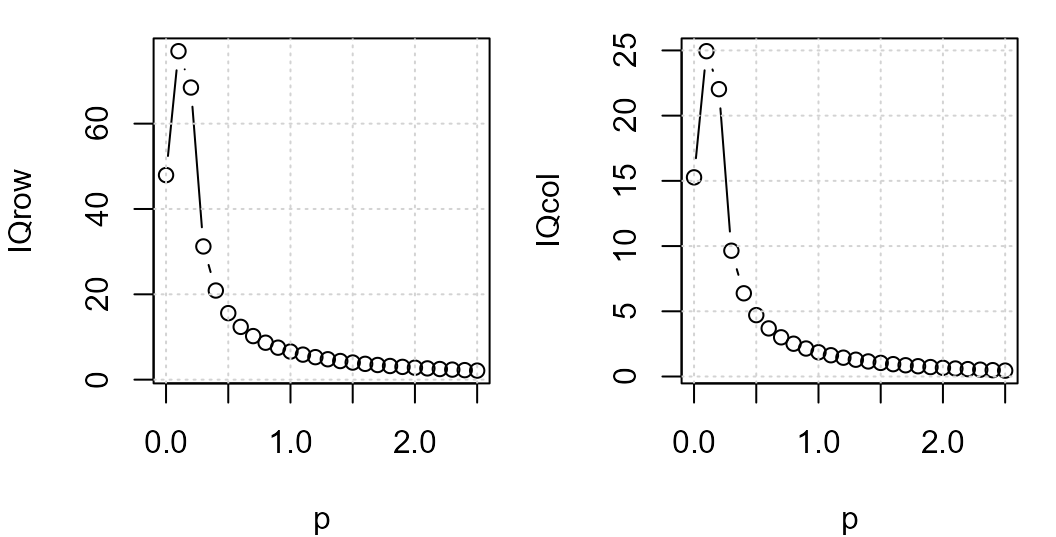

Klawonn et al.2 propose a method for honing in on the optimal power transformation by finding the one that maximizes each effect’s spreads vis-a-vis the residuals. They do this by computing the ratio between the interquartile range of the row an column effects to the 80% quantile of the residual’s absolute values.

The following code chunk computes this ratio for different power transformations.

f1 <- function(x){

out <- eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings,

p = x, plot=FALSE, tukey = FALSE)

c(p=out$power, IQrow = out$IQ_row, IQcol = out$IQ_col)

}

IQ <- t(sapply(0:25/10, FUN = f1 )) # Apply transformations at 0.1 intervals

plot(IQrow ~ p, IQ, type="b")

grid()

plot(IQcol ~ p, IQ, type="b")

grid()

Row (left) and column (right) effect IQRs to residuals ratio vs power.

The plot suggests a power transformation of 0.1. We’ll re-run the median polish using this power transformation.

M4 <- eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings,

plot = FALSE, p = 0.1)

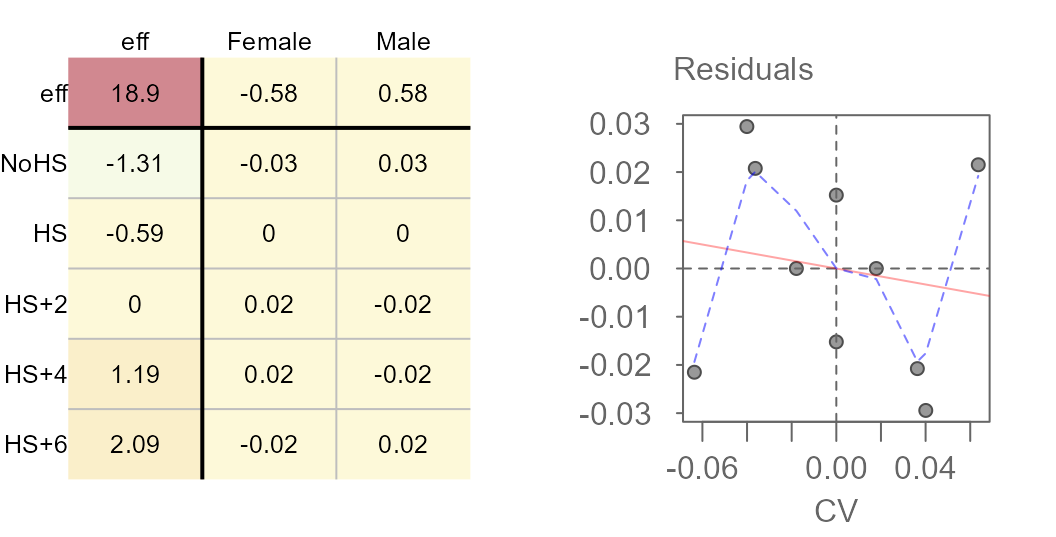

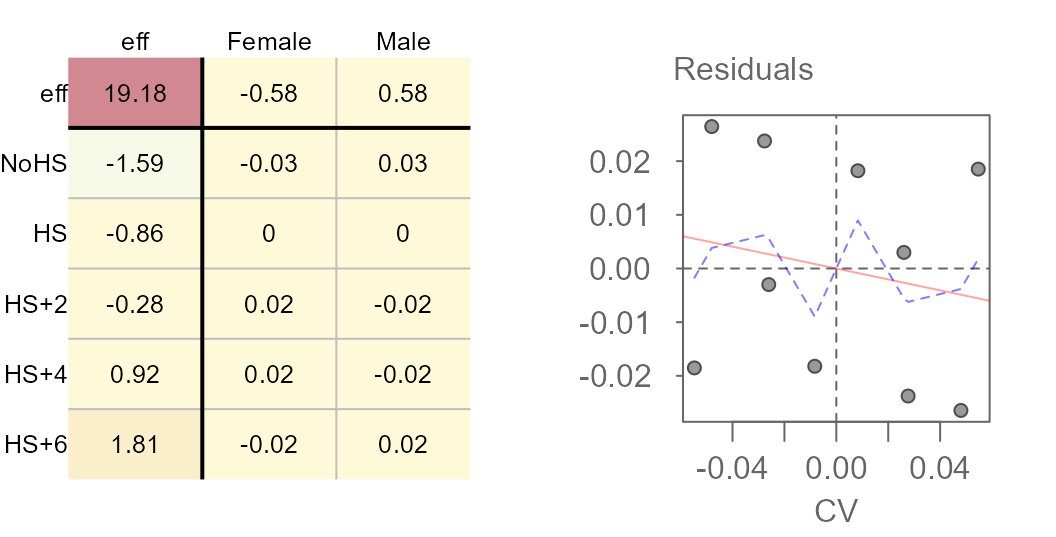

plot(M4, res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

plot(M4, "diagnostic")

The slope is much smaller and the loess fit suggests no monotonically increasing or decreasing relationship between the residuals and the CV values. Re-expressing the value seems to have done a good job in stabilizing the residuals across CV values.

We’ll modify the color scheme so as to place emphasis on the effects as opposed to the overall value.

plot(M4, col.com = FALSE,

res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

Here’s what we can glean from the output:

- The earnings values are best expressed on a power scale of 0.1.

- Overall, the median earnings (in re-expressed form) is about $19.

- Variability in earnings due to different levels in education attainment covers a range of $3 while that for different sexes covers a range of $1.

- The residuals are much smaller relative to the effects when the earnings are re-expressed. The residuals explain close to $5 of the variability in the data. Just about all of the variability can be explained by the effects.

- Re-expressing the values eliminates any interaction between the effects.

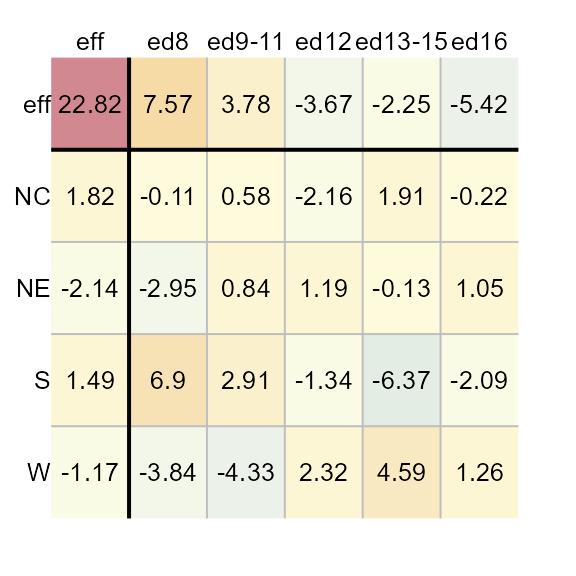

The mean polish

The eda_pol function accepts any statistical summary

function. By default, it uses the median. For example, the mean

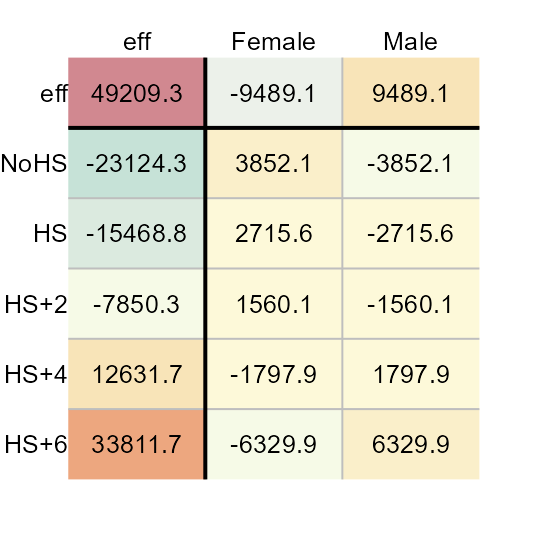

polish generated from the earnings dataset looks like this:

M5 <- eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings ,

stat = mean, plot = FALSE)

plot(M5, res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

Polishing the data using the mean requires a single iteration to reach a stable output. The mean suffers from its sensitivity to non-symmetrical distributions and outliers. As such, the median polish is a more robust summary statistic. That said, running the mean polish has its benefits: It’s a great way to represent the effects generated from a two-way analysis of variance (aka 2-way ANOVA). This is confirmed by comparing the above row and column effects to a traditional 2-way ANOVA technique shown here:

model.tables(aov(Earnings ~ Sex + Education, income))

Tables of effects

Sex

Sex

Female Male

-9489 9489

Education

Education

NoHS HS HS+2 HS+4 HS+6

-23124 -15469 -7850 12632 33812As with the median polish, we must concern ourselves with interactions between the effects. If interaction is present, ANOVA inferential statistics using the F-test can be untrustworthy.

plot(M5, plot = "diagnostic", res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

There is strong evidence of interaction. The slope of 0.92 can be used to estimate a power transformation via \(1 - slope\). This is close to the power transformation of 0.1 we ended up adopting in the median polish exercise.

M4b <- eda_pol(income, row = Education, col = Sex, val = Earnings , stat = mean,

plot = FALSE, p = 0.1, maxiter = 1)

plot(M4b, res.size = 0.8, row.size = 0.8, col.size = 0.8)

plot(M4b, "diagnostic")

Results of a mean polish (left) and its diagnositc plot (right).

Re-expressing the data does a nice job in removing the interaction between effects much like it did when we performed the median polish. This suggests that if one were to run a two-way ANOVA, a re-expression would be strongly suggested.