The empirical QQ plot (and derived Tukey mean-difference plot)

Manuel Gimond

2025-07-09

Source:vignettes/qq.Rmd

qq.RmdIntroduction

The empirical quantile-quantile plot (QQ plot) is probably one of the most underused and least appreciated plots in univariate analysis. It is used to compare two distributions across their full range of values. It is a generalization of the boxplot in that it does not limit the comparison to just the median and upper and lower quartiles. In fact, it compares all values by matching each value in one batch to its corresponding quantile in the other batch. The sizes of each batch need not be the same. If they differ, the larger batch is interpolated down to the smaller batch’s set of quantiles.

A QQ plot does not only help visualize the differences in distributions, but it can also model the relationship between both batches. Note that this is not to be confused with modeling the relationship between a bivariate dataset where the latter pairs up the points by observational units whereas a QQ plot pairs up the values by their matching quantiles.

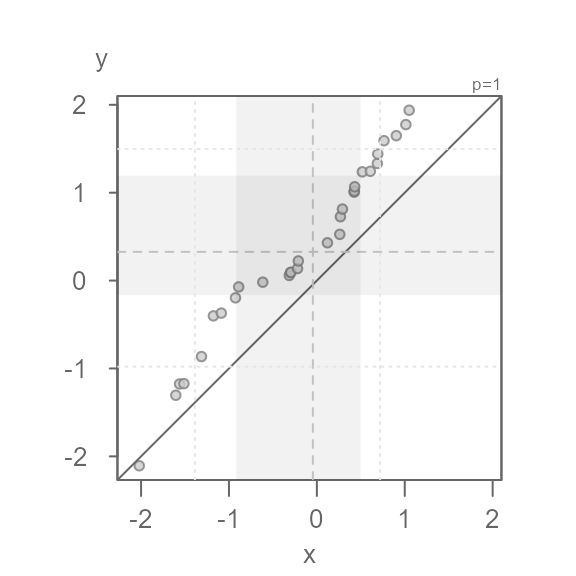

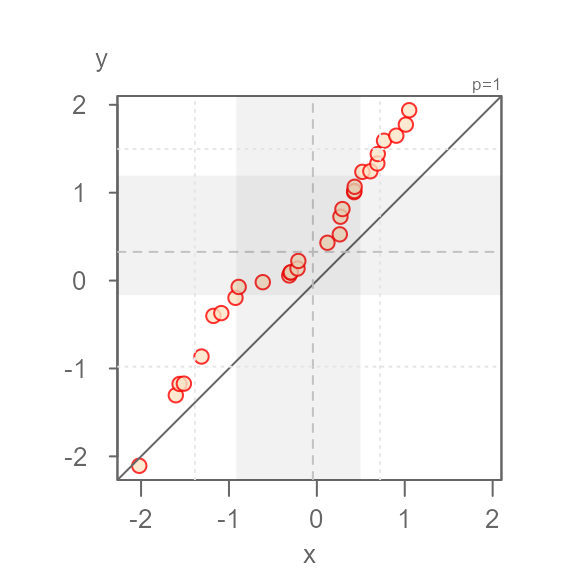

Anatomy of the eda_qq plot

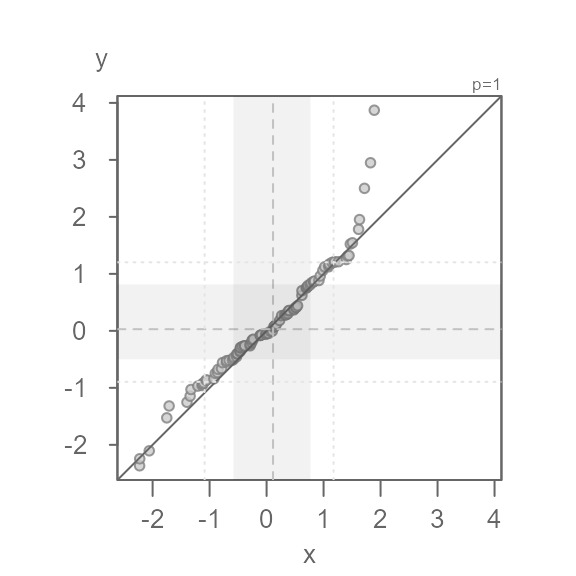

#> [1] "Suggested offsets:y = x * 1.4573 + (0.9914)"- Each point represents matching quantiles from each batch.

- The shaded region represent each batch’s middle values ( 75% of middle values by default).

- The dashed lines inside the shaded boxes represent each batch’s medians.

- The upper right-hand text indicates the power

transformation applied to the both batches (default is a power of

1which is original measurement scale). If a formula is applied to one or both batches, it too will appear in the upper right-hand text. - The

eda_qqwill also output the suggested relationship between the y variable and the x variable in the console. It bases this on each batch’s interquartile values. - If the output is assigned to a new object, that object will store a

list of the following values: the

xvalue (interpolated if needed), theyvalue (interpolated if needed), the power parameter (p), the formula applied to the x variable, and the formula applied to the y variable.

An overview of some of the function arguments

Data type

The function will accept a dataframe with a column of the

quantitative variable of interest, and a column of the category each

measurement belongs to. It will also accept two separate vector

objects. For example, to pass two separate vector object,

x and y, type:

If the data are in a dataframe, type:

dat <- data.frame(val = c(x, y), cat = rep(c("x", "y"), each = 30))

eda_qq(dat, val, cat)

Suppressing the plot

You can suppress the plot and have the x and y values outputted to a

list in the data dataframe. If the batches did not match in

size, the output will show their interpolated values such that the

output batches match in size.

The output will also include the power parameter applied to both

batches as well as any formula applied to one or both batches

(fx is the formula applied to the x variable and

fy is the formula applied to the y variable).

Q <- eda_qq(x,y, plot = FALSE)

#> [1] "Suggested offsets:y = x * 1.12 + (0.5619)"

Q

#> $data

#> x y

#> 1 -2.0207122 -2.10710669

#> 2 -1.6048333 -1.30465821

#> 3 -1.5620907 -1.17618932

#> 4 -1.5128732 -1.17253191

#> 5 -1.3126378 -0.86423268

#> 6 -1.1770882 -0.40162859

#> 7 -1.0871906 -0.37002087

#> 8 -0.9258832 -0.19629536

#> 9 -0.8896555 -0.07210822

#> 10 -0.6152073 -0.01829722

#> 11 -0.3140113 0.05826287

#> 12 -0.2996734 0.09105884

#> 13 -0.2954234 0.09371398

#> 14 -0.2199849 0.13698992

#> 15 -0.2108781 0.22318119

#> 16 0.1202060 0.43006689

#> 17 0.2608893 0.52597363

#> 18 0.2680445 0.72665767

#> 19 0.2910663 0.81351407

#> 20 0.4239690 1.00612388

#> 21 0.4262605 1.01831440

#> 22 0.4301416 1.06713353

#> 23 0.5176361 1.23708449

#> 24 0.6085180 1.24360530

#> 25 0.6880919 1.33232007

#> 26 0.6929772 1.43973056

#> 27 0.7640838 1.59125312

#> 28 0.9037644 1.64852115

#> 29 1.0124869 1.77464625

#> 30 1.0503544 1.93823390

#>

#> $p

#> [1] 1

#>

#> $fx

#> NULL

#>

#> $fy

#> NULLDefining the grey region

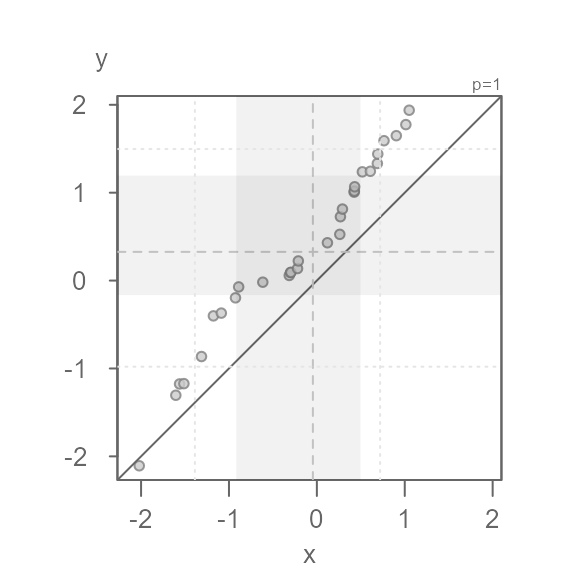

The grey region highlights the core of both batches. By default, this

is set to 75%. Its boundaries can be modified via the inner

argument.

For example, to highlight the mid 68% of values, type:

eda_qq(x, y, inner = 0.68)

You can suppress the plotting of the shaded region by setting

q = FALSE.

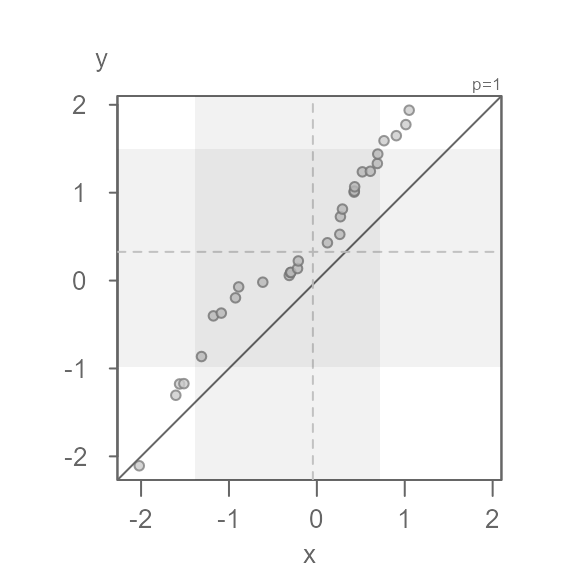

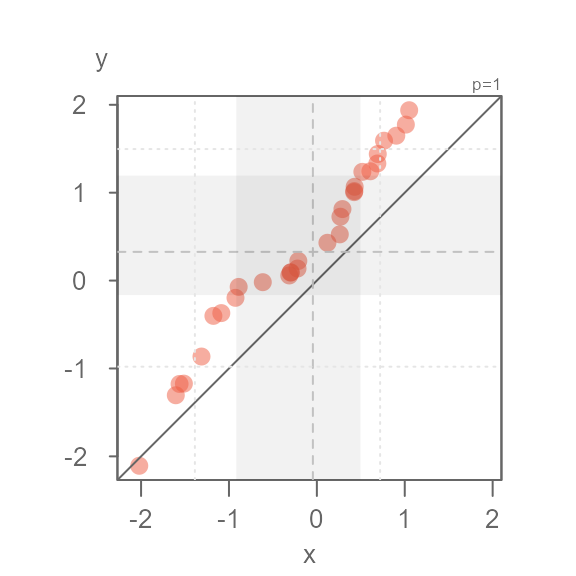

Applying different symbol to tail-end points

If the grey region is too distracting, but you still wish to

distinguish identify the inner core values from the tail-end values, you

can set tails = TRUE to enable to the point symbol option,

and q = FALSE to remove the grey region.

eda_qq(x, y, tails = TRUE, q = FALSE)

By default, the tail-end points are symbolized using an open point

symbol (as opposed to a filled point symbol applied t the inner core

points). The tail-end point symbol can be modfied via the

tail.pch, tail.col andtail.fill

arguments. For example, to change the tail-end point symbol to a

+ symbol, type:

eda_qq(x, y, tails = TRUE, q = FALSE, tail.pch = 3)

If you want greater emphasis to be placed on the inner core points, change its symbol color. For example:

eda_qq(x, y, tails = TRUE, q = FALSE, tail.pch = 3, p.fill = "coral3")

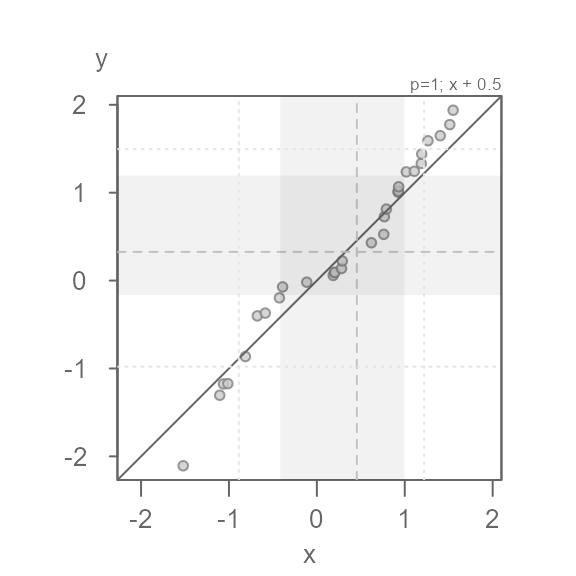

Applying a formula to one of the batches

You can apply a formula to a batch via the fx argument

for the x-variable and the fy argument for the y-variable.

The formula is passed as a text string. For example, to add

0.5 to the x values, type:

eda_qq(x, y, fx = "x + 0.5")

Quantile type

There are many different quantile algorithms available in R. To see

the full list of quantile types, refer to the quantile help page:

?quantile. By default, eda_qq() adopts

q.type = 5. In general, the choice of quantiles will not

really matter, especially for large datasets. If you want to adopt R’s

default type, set q.type = 7.

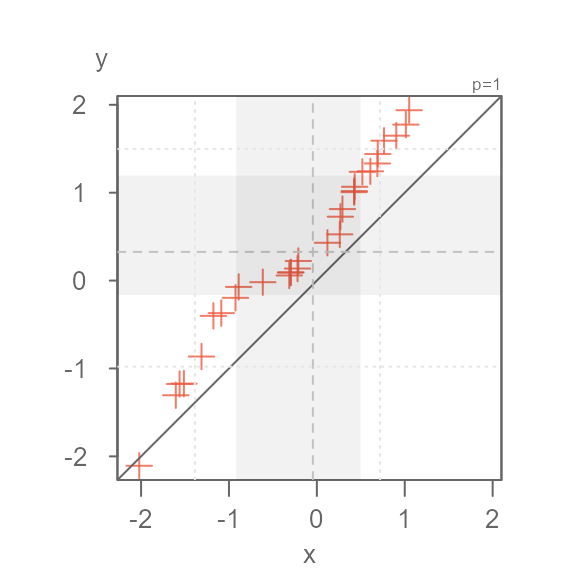

Point symbols

The default point type, color and size applied to all points

(or just the inner core points if tails = TRUE) can be

modified via the pch, p.col (and/or

p.fill) and size arguments. The color can be

either a built-in color name (you can see the full list by typing

colors()) or the rgb() function. If you define

the color using one of the built-in color names, you can adjust its

transparency via the alpha argument. An alpha

value of 0 renders the point completely transparent and a

value of 1 renders the point completely opaque. The point

symbol can take on two color parameters depending on point type. If

pch is any number between 21 and 25, p.fill

will define its fill color and p.col will define its border

color. For any other point symbol type, the p.fill argument

is ignored.

Here are a few examples:

eda_qq(x, y, p.fill = "bisque", p.col = "red", size = 1.2)

eda_qq(x, y, pch = 16, p.col = "tomato2", size = 1.5, alpha = 0.5)

eda_qq(x, y, pch = 3, p.col = "tomato2", size = 1.5)

Interpreting a QQ plot

To help interpret the following QQ plots, we’ll compare each plot to its matching kernel density plot.

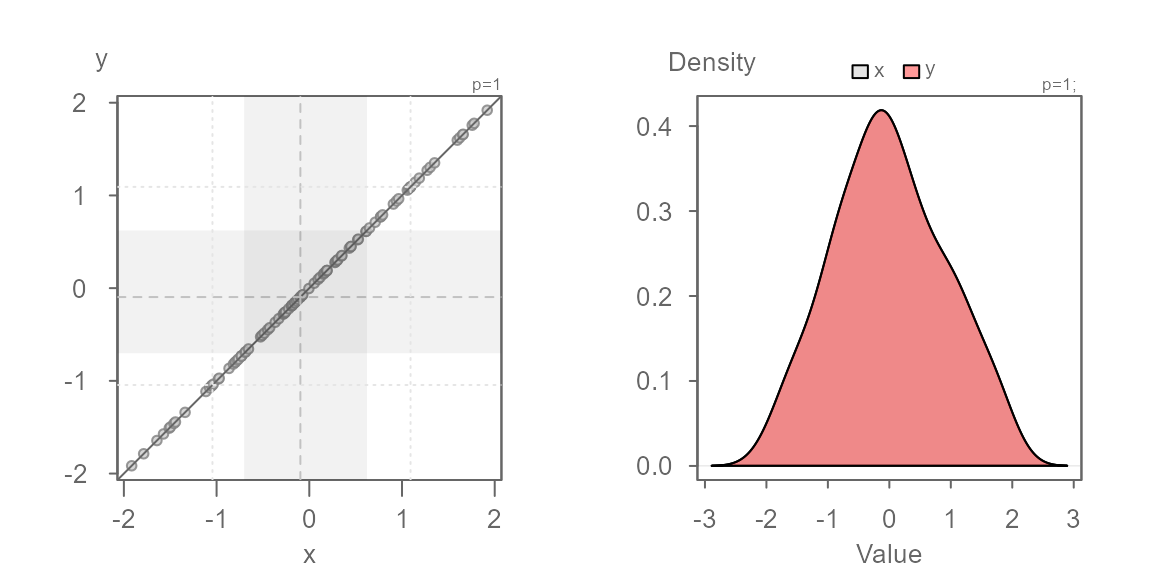

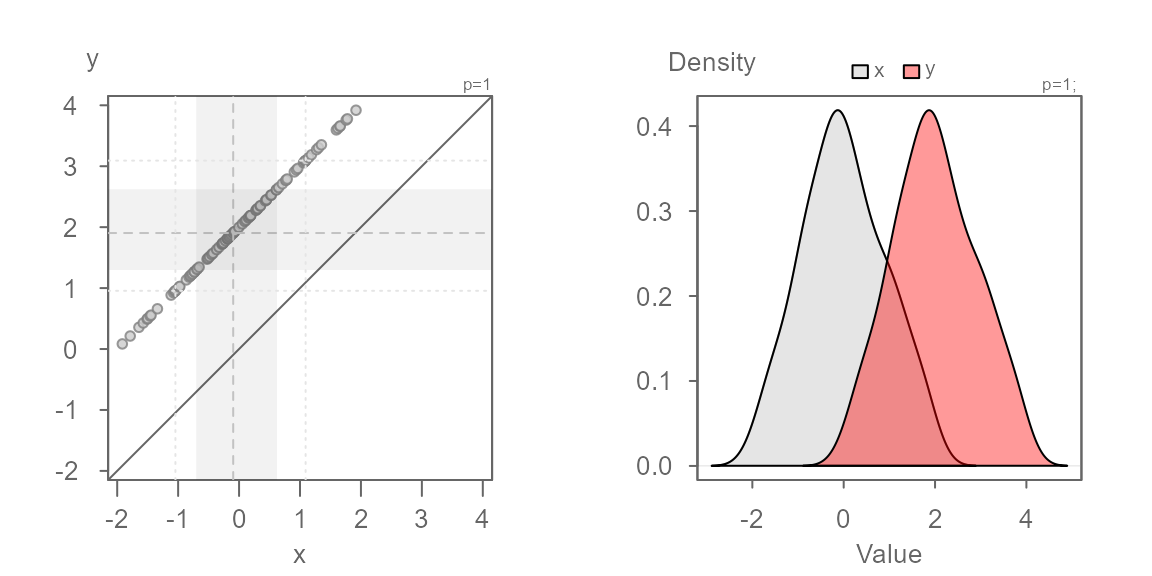

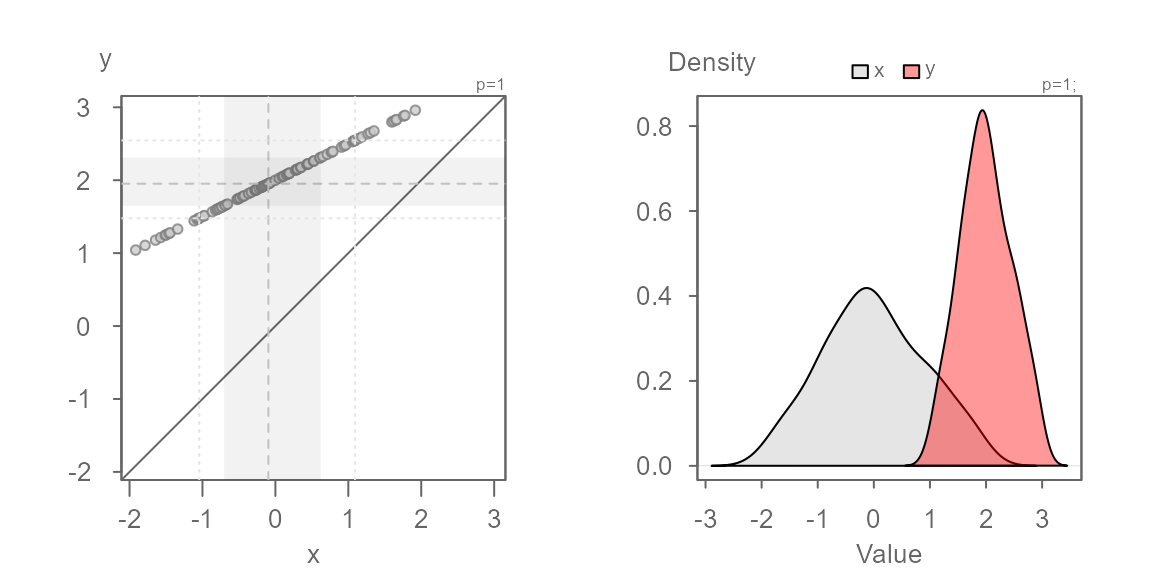

Identical distributions

In this first example, we will generate a QQ plot of two identical distributions.

When two distributions are identical, the points will line up along the `\(x=y\) line as shown above. This will also generate overlapping density plots as seen on the right plot.

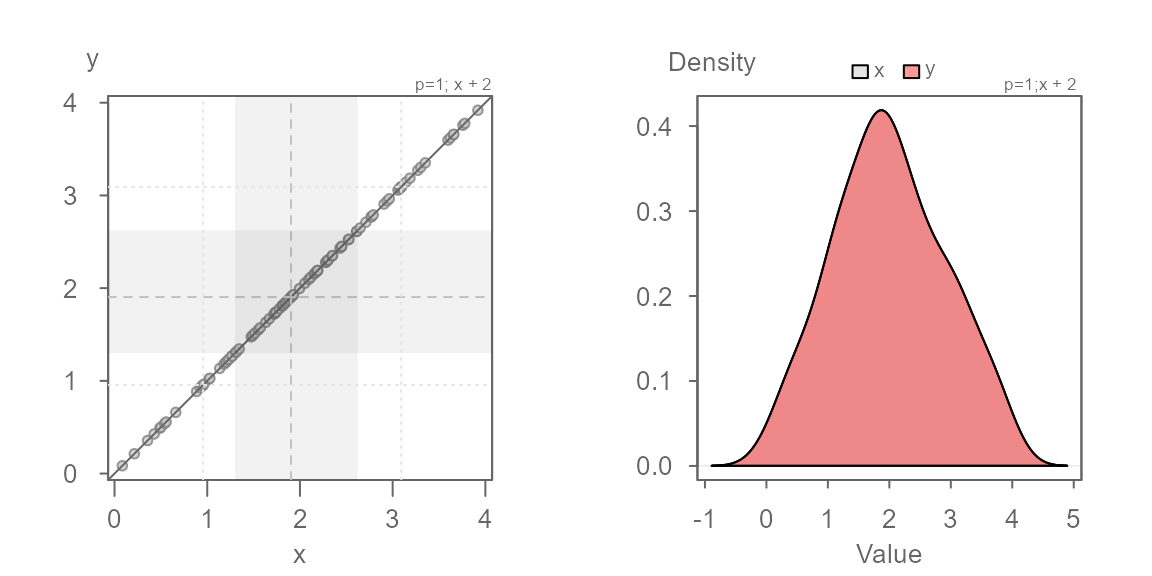

Additive offset

We will work off of the same batches, but this time we will offset

the second batch, y, by 2. This case is

referred to as an additive offset.

You’ll note that the points are parallel to the \(x=y\) line. This indicates that the

distributions have the exact same shape. But, they do not fall on the

\(x=y\) line–they are offset by

+2 units when measured along the y-axis, as expected. We

can confirm this by adding 2 to the x

batch:

The points now overlap the \(x=y\) line perfectly. The density distribution overlap exactly as well.

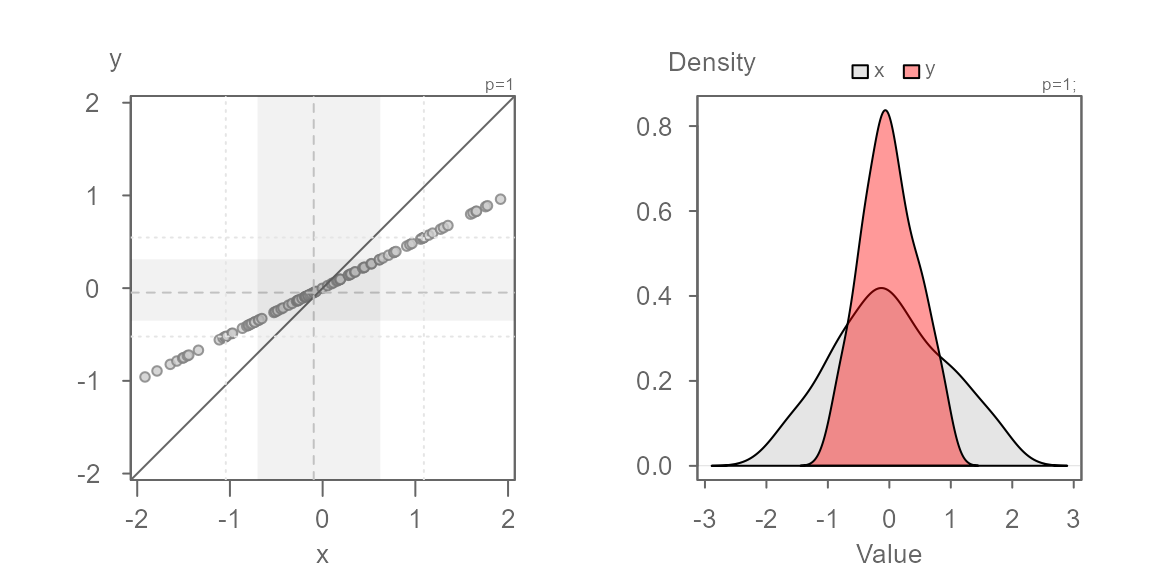

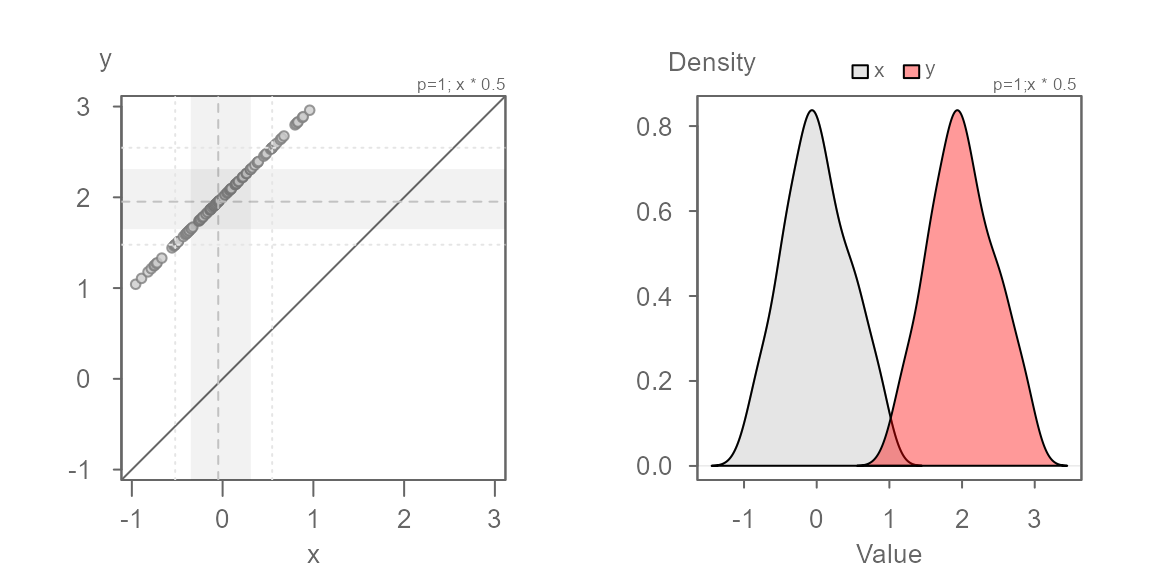

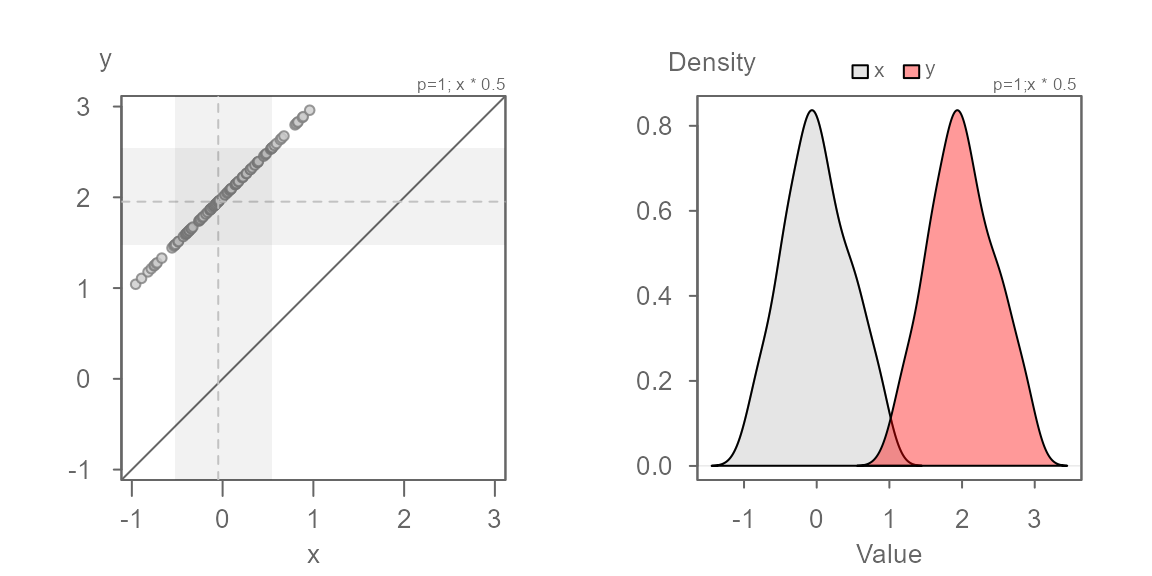

Multiplicative offset

Next, we explore two batches that share the same central value but

where the second batch is 0.5 times that of the first. This

case is referred to as a multiplicative offset.

Here, the series of points are at an angle of the \(x=y\) line yet, you’ll note that the points

follow a perfectly straight line. This suggests a multiplicative offset

with no change in location. This indicates that the “shape” between the

batches are similar, but that one is “wider” than the other. Here,

y is half as wide as x. We can also state that

x is twice as wide as y

We know the multiplicative offset since we synthetically generated

the values x and y. But in practice eyeballing

the multiplier from the plot is not straightforward. We can use the

suggested offset of 0.5 displayed in the console to help

guide us. We can also use the angle between the points and the \(x=y\) line to judge the direction to take

when choosing a multiplier. If the points make up an angle that is less

than the \(x=y\) line, we want to

choose an x multiplier that is less than 1. If

the angle is greater than the \(x=y\)

line, we want to choose a multiplier that is greater than

1.

Here, we know that the multiplier is 0.5. Let’s confirm

this with the following code chunk:

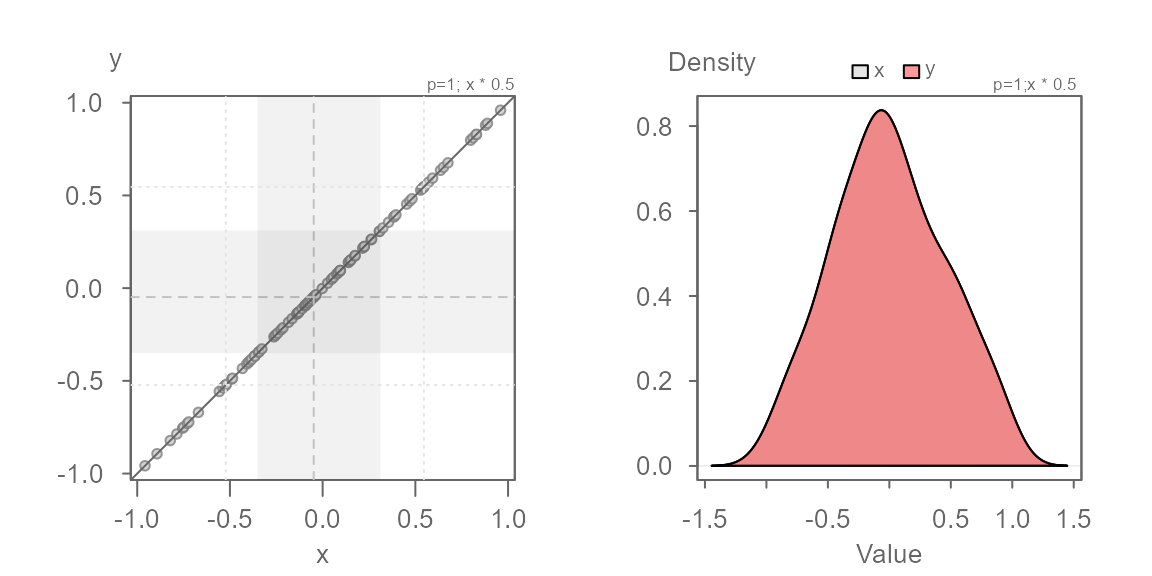

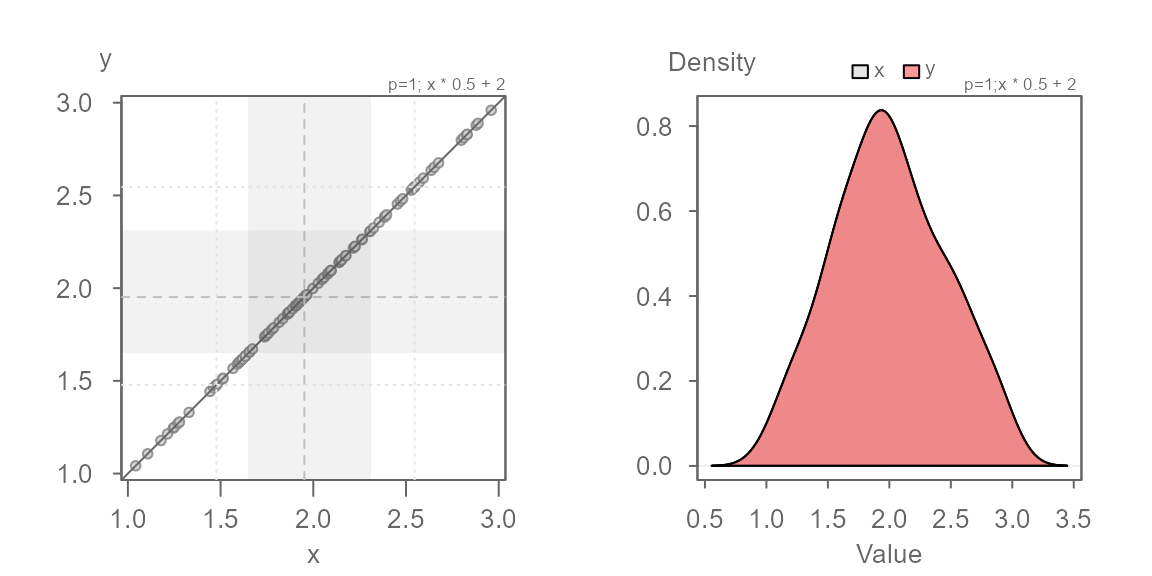

Both additive and multiplicative offset

In this next example, we add both a multiplicative and an additive offset to the data.

We now see both a multiplicative offset (the points form an angle to the \(x=y\) line) and an additive offset (the points do not intersect the \(x=y\) line). This suggests that the width of the batches differ and that their values are offset by a constant value across the full range of values. It’s usually best to first identify the multiplicative offset such that the points are rendered parallel to the \(x=y\) line. Once the multiplier is identified, we can then identify the additive offset.

No surprise, the multiplier of 0.5 renders the series of

points parallel to the \(x=y\) line. We

can now eyeball the offset of +2 when measuring the

distance between any of the points and the \(x=y\) line when measured along the

y-axis.

We can model the relationship between y and x as \(y = x * 0.5 + 2\).

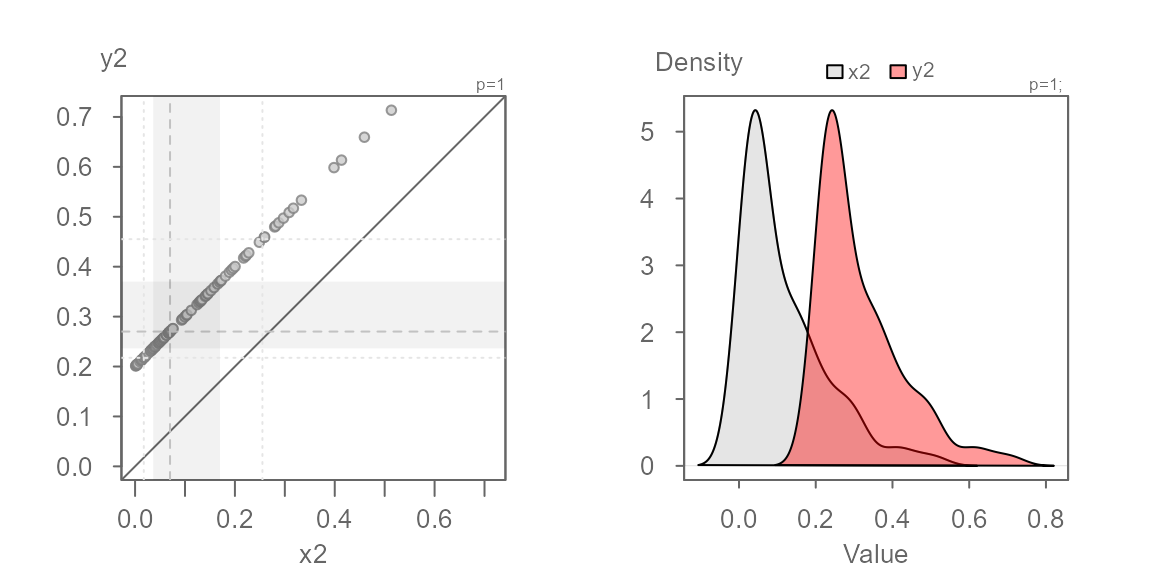

Batches need not be symmetrical

So far, we have worked with a normally distributed dataset. But note that any distribution can be used in a QQ plot. For example, two equally skewed distributions that differ by their central values will generate points that are perfectly lined up.

Since both distributions have an identical shape, the points will follow a straight line regardless of the nature of the shape (skewed, unimodal, bimodal, etc…).

When distributions are not symmetrical, you should be careful in not letting the long tails of the distribution bias your interpretation of the plots given that the tail-end values will take up a disproportionately larger portion of the plot. Tail-end values tend to be noisy and will undoubtedly generate a QQ plot that may suggest that the distributions are inherently dissimilar. For example, if we generate a plain vanilla plot (i.e. one without the built-in inner core guides) of two batches pulled from an identical theoretical distribution, we get the following QQ plot.

Note how the tail-end values deviate from the \(x=y\) line. They take up nearly a third of the plot leading one to place a disproportionate emphasis on these values. Adding the grey regions and the median value lines helps us identify the bulk of the data (inner 75% by default).

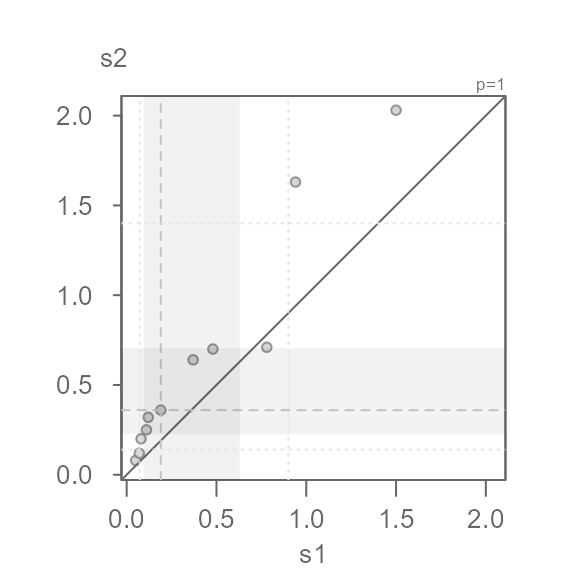

Power transformation

The eda_qq function allows you to apply a power

transformation to both batches. Note that transforming just one batch

makes little sense since you end up comparing two batches measured on a

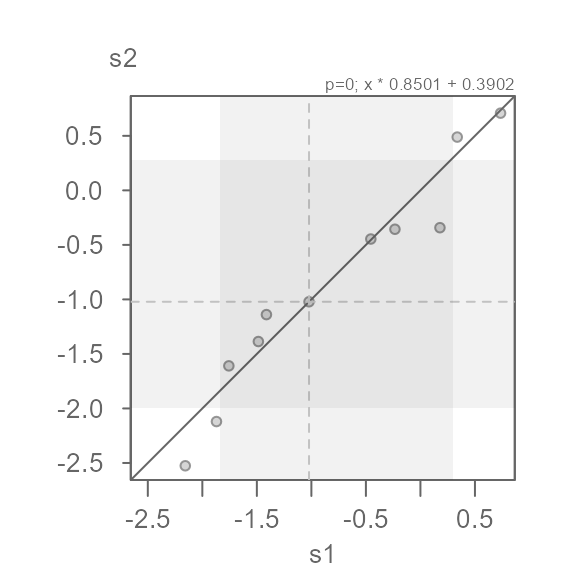

different scale. In this example, we make use of R’s

Indometh dataset where we compare indometacin plasma

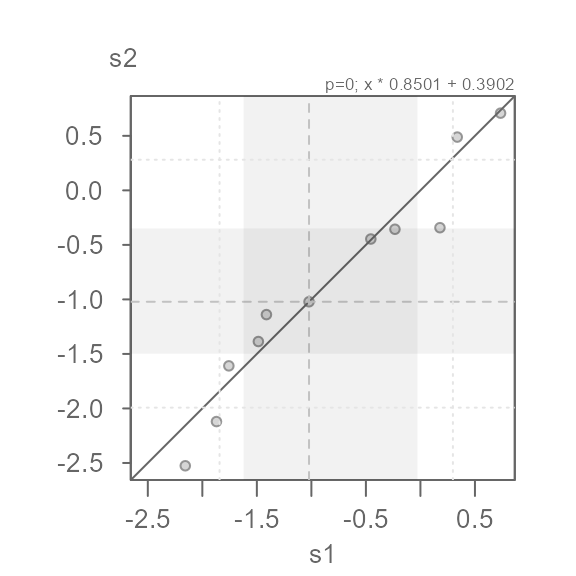

concentrations between two test subjects.

s1 <- subset(Indometh, Subject == 1, select = conc, drop = TRUE) # Test subject 1

s2 <- subset(Indometh, Subject == 2, select = conc, drop = TRUE) # Test subject 2

eda_qq(s1, s2)

The QQ plot’s shaded regions are shifted towards lower values. The

shaded regions show the mid 75% of values for each batch. When the

regions are shifted towards lower values or higher values, this suggests

skewed data. Another telltale sign of a skewed dataset is the gradual

dispersion of the points in any of the two diagonal directions. Here, we

go from a relatively high density of points near the lower values and a

lower density of points near higher values. This does not preclude us

from identifying multiplicative/additive offsets, but many statistical

procedures benefit from a symmetrical distribution. Given that the

values are measures of concentration, we might want to adopt a

log transformation. The power transformation is defined

with the p argument (a power parameter value of

0 defines a log transformation).

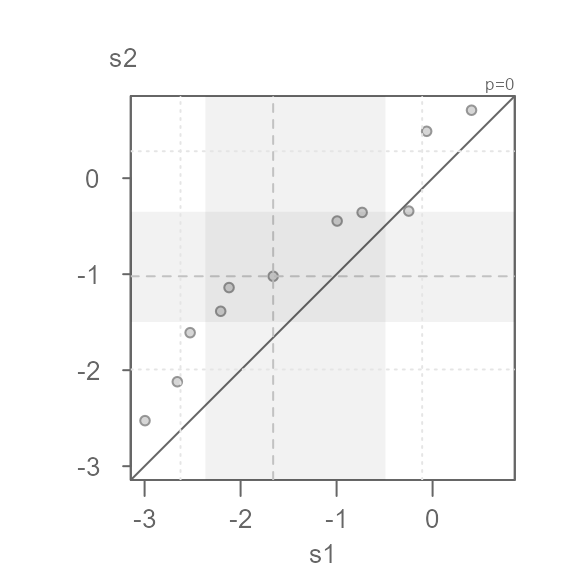

eda_qq(s1, s2, p = 0)

#> [1] "Suggested offsets:y = x * 0.8508 + (0.3914)"This seems to do a decent job of symmetrizing both distributions.

Note that the suggested offset displayed in the console applies to the transformed dataset. We can verify this by applying the offset to the x batch.

eda_qq(s1, s2, p = 0, fx = "x * 0.8501 + 0.3902")

We can characterize the differences in indometacin plasma concentrations between subject 1 and subject 2 as \(log(conc)_{s2} = log(conc)_{s1} * 0.8501 + 0.3902\)

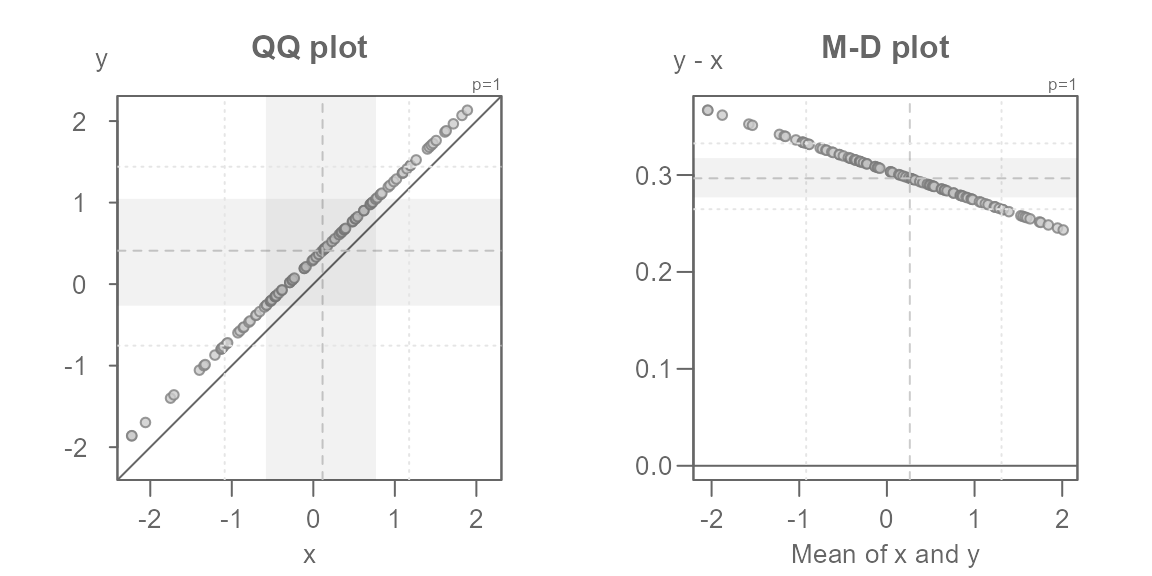

The Tukey mean-difference plot

The Tukey mean-difference plot is simply an

extension of the QQ plot whereby the plot is rotated such that the \(x=y\) line becomes horizontal. This can be

useful in helping identify subtle differences between the point pattern

and the line. The plot is rotated 45° by mapping the difference between

both batches to the y-axis, and mapping the mean between both

batches to the x-axis. For example, the following figure on the left

(the QQ plot) shows the additive offset between both batches but it

fails to clearly identify the multiplicative offset. The latter can be

clearly seen in the Tukey mean-difference plot (on the right) which is

invoked by setting the argument md = TRUE.

set.seed(321)

x <- rnorm(10)

y <- x * 0.97 + 0.3

eda_qq(x, y, title = "QQ plot")

eda_qq(x, y, md = TRUE, title = "M-D plot")

Note that the mean-difference plot highlights the mid

difference values defined by the inner argument.

This does not clearly reflect the mid values shown in the QQ plot. If

you want the mean-difference plot to show the inner core values, set

tails to TRUE. In doing so, you might want to

disable the shaded region to have most of the emphasis placed on the

points.

eda_qq(x, y, md = TRUE, tails = TRUE, q = FALSE)

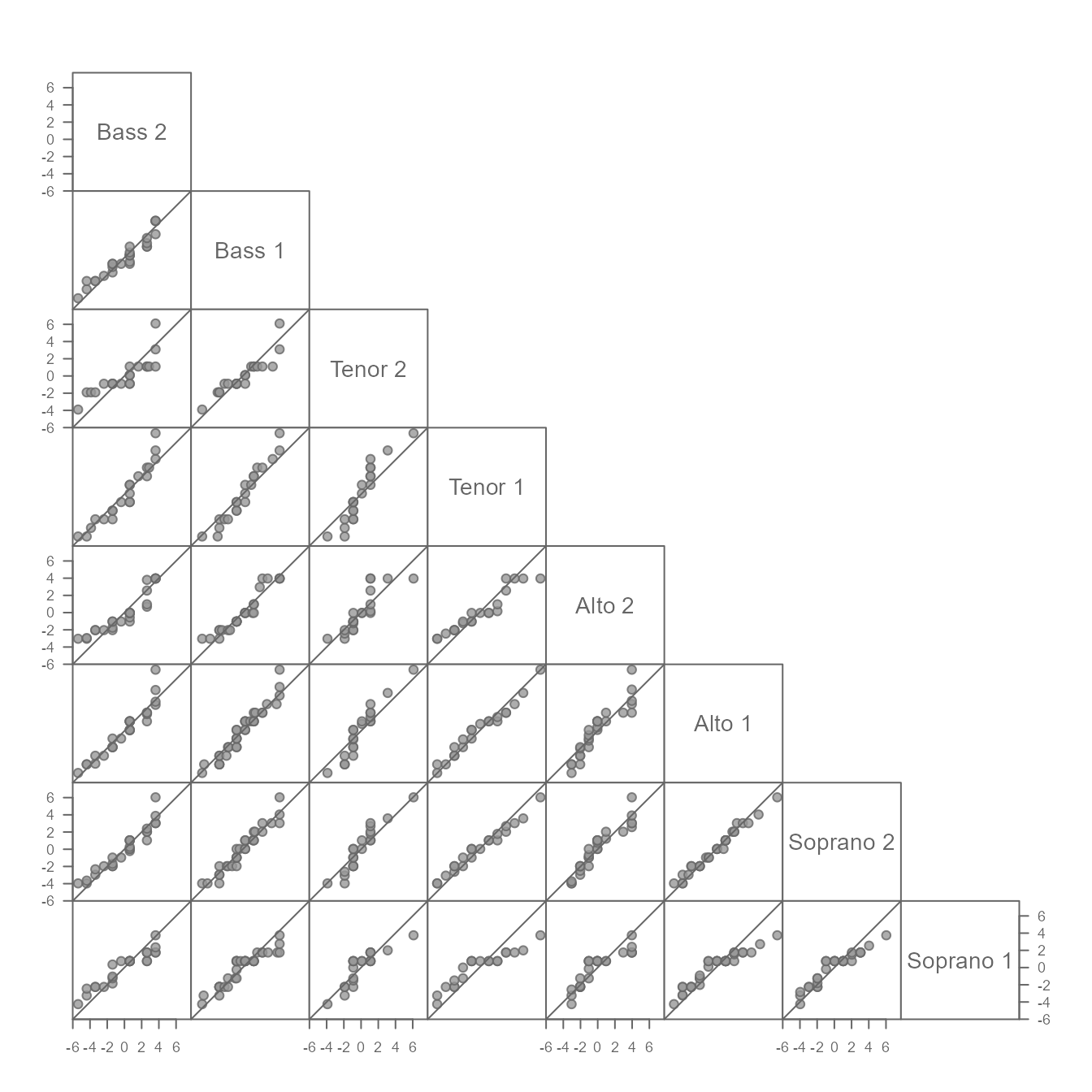

Creating a QQ plot matrix

A separate function, eda_qqmat, is used to create a QQ

plot matrix. It adopts many of the same arguments available in the

eda_qq function, but it does not adopt some of

eda_qq’s default settings. For example, the inner region

shading parameter q is set to FALSE–this to

minimize clutter in the densely packed matrix. Instead, points Falling

outside of the inner region are symbolized with an open point

symbol. For example, to generate an empirical QQ plot matrix of singer

height values conditioned of voice parts type:

You can, of course, adopt the same point symbol for all points by

setting tails = FALSE.

The matrix limits the output to the lower triangle given that the

matrix is symmetrical. If you wish to add the upper triangle, set

upper = TRUE.

Additive offsets can be distracting if the goal is to compare spreads

across each group. The function offers the option to generate a

residuals QQ plot matrix (resid = TRUE) by subtracting the

input values with the group mean (stat = mean) or median

(stat = median). For example, to generate a residuals QQ

plot of singer height, type:

eda_qqmat(singer, height, voice.part, resid = TRUE)

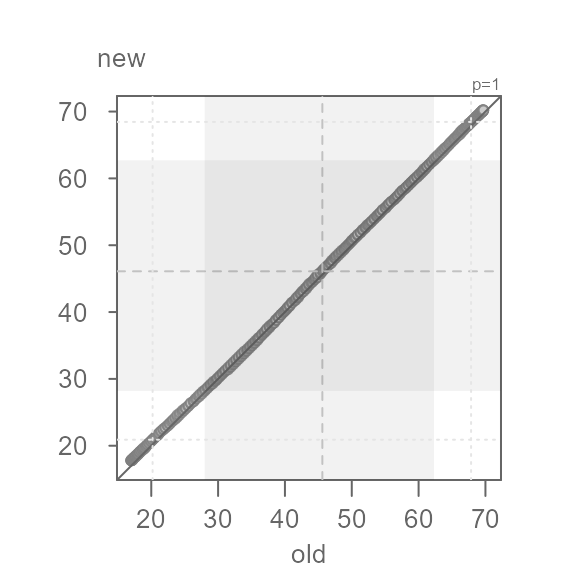

A working example

Many datasets will have distributions that differ not only additively

and/or multiplicatively, but also by their general shape. This may

create complex point patterns in your QQ plot. Such cases can be

indicative of different processes at play for different ranges

of values. We’ll explore such a case using wat95 and

wat05 datasets available in this package. The data

represent derived normal temperatures for the 1981-2010 period

(wat95) and the 1991-2020 period (wat05) for

the city of Waterville, Maine (USA). We will subset the data to the

daily average normals, avg:

old <- wat95$avg # legacy temperature normals

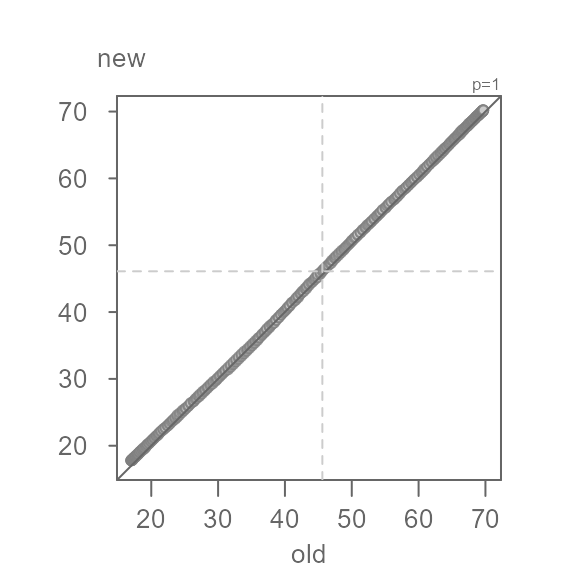

new <- wat05$avg # current temperature normalsWe will now compare their distributions. We’ll omit the shaded region for now.

Q <- eda_qq(old, new, q = FALSE)

At first glance, the batches do not seem to differ. But how close are

the points to the \(x=y\) line? We will

rotate the plot to zoom in on the \(x=y\) line by setting

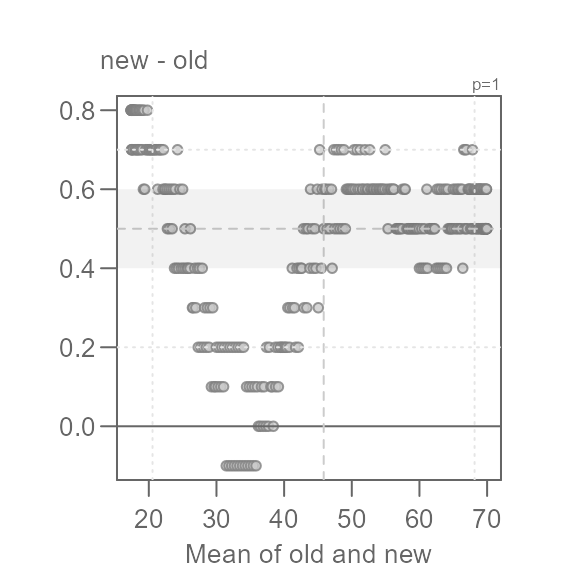

md = TRUE.

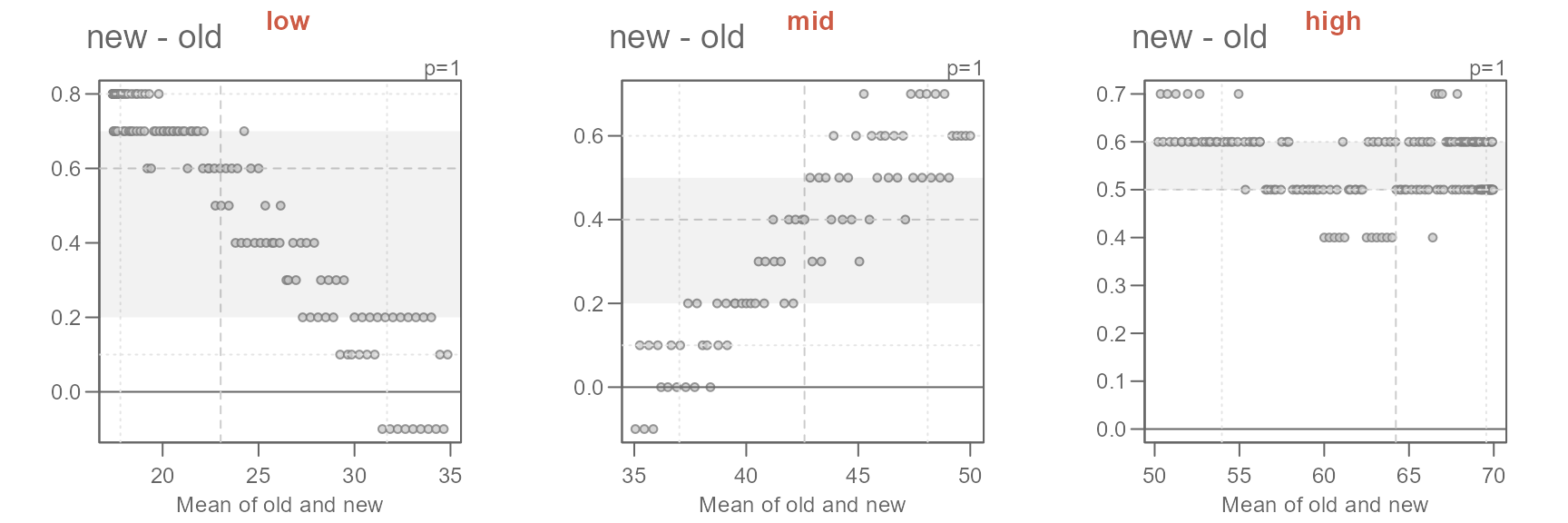

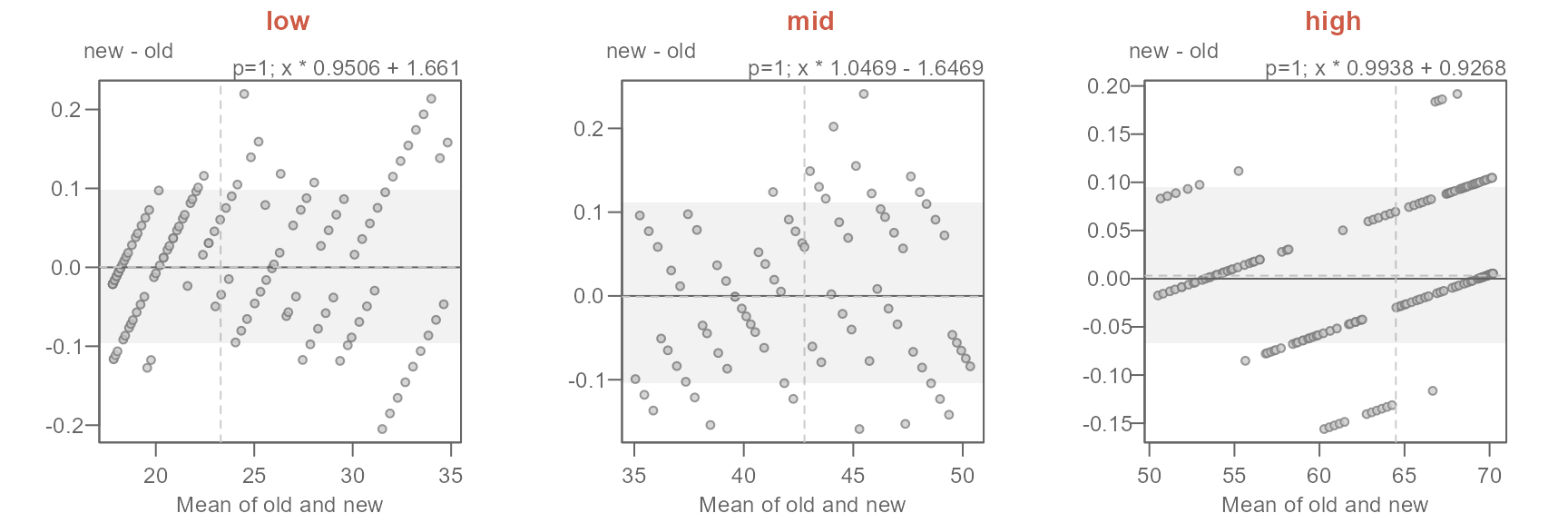

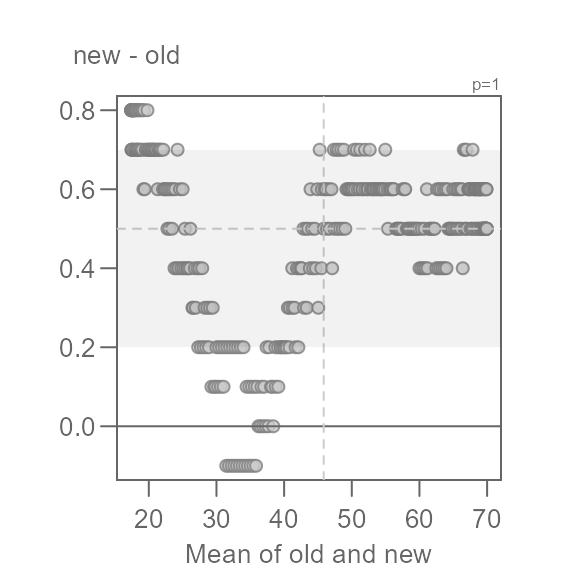

Q <- eda_qq(old, new, md = TRUE)

This view is proving to be far more insightful. Note that for most of

the data, we have an overall offset of 0.5 suggesting that the new

normals are about 0.5°F. warmer. We could stop there, but the pattern

observed in the Tukey mean-difference plot is far from random. In fact,

we can break the pattern into three distinct ones at around 35°F and

50°F. We will categorize these groups as low,

mid and high values.

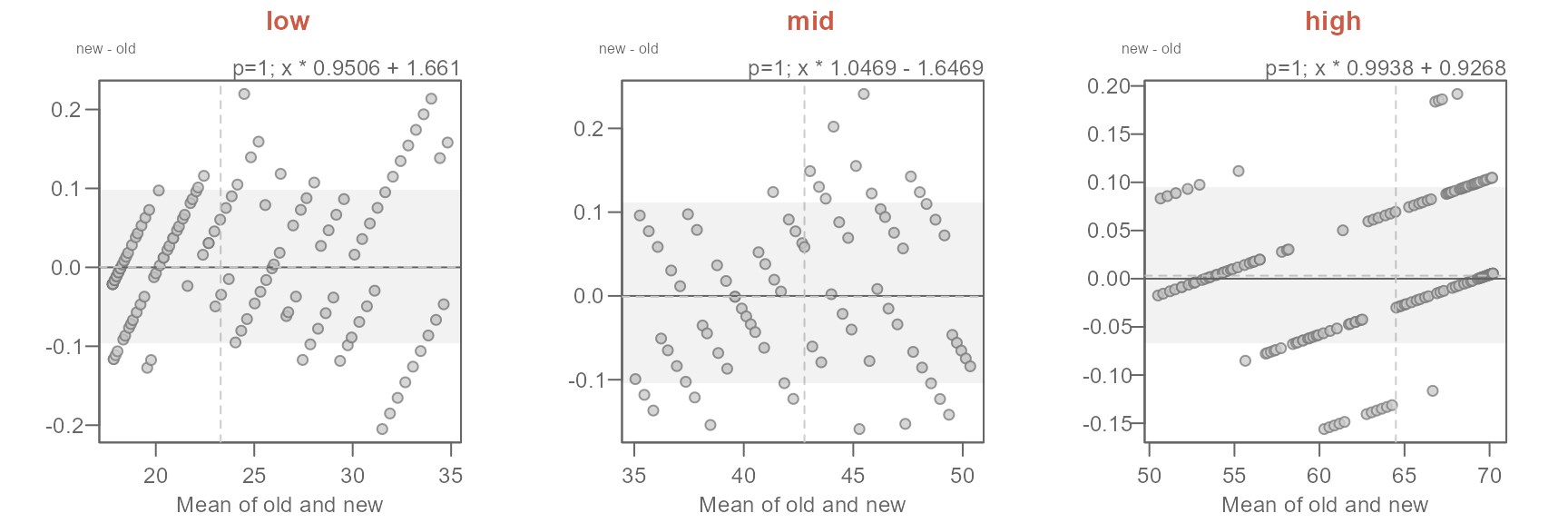

This next chunk of code will generate three separate QQ plots for each range of values.

labs <- c("low", "mid", "high")

out <- Q$data

out$avg <- (out$old + out$new) / 2

out2 <- split(out, cut(out$avg, c(min(out$avg), 35, 50, max(out$avg)),

labels = labs, include.lowest = TRUE))

sapply(labs, FUN = \(x) {eda_qq(out2[[x]]$old, out2[[x]]$new ,

xlab = "old", ylab = "new", md = T)

title(x, line = 3, col.main = "orange")} )

#> [1] "Suggested offsets:y = x * 0.9507 + (1.6599)"

#> [1] "Suggested offsets:y = x * 1.047 + (-1.6502)"

#> [1] "Suggested offsets:y = x * 0.9938 + (0.9268)"The suggested offsets are displayed in the console for each group.

It is important to note that we are splitting the paired values generated from the earlier

eda_qqfunction (out$avg) and not the values from the original datasets (oldandnew). Had we split the original data prior to combining them witheda_qq, we could have generated different patterns in the QQ and Tukey plots. This is because this approach could generate different quantile pairs.

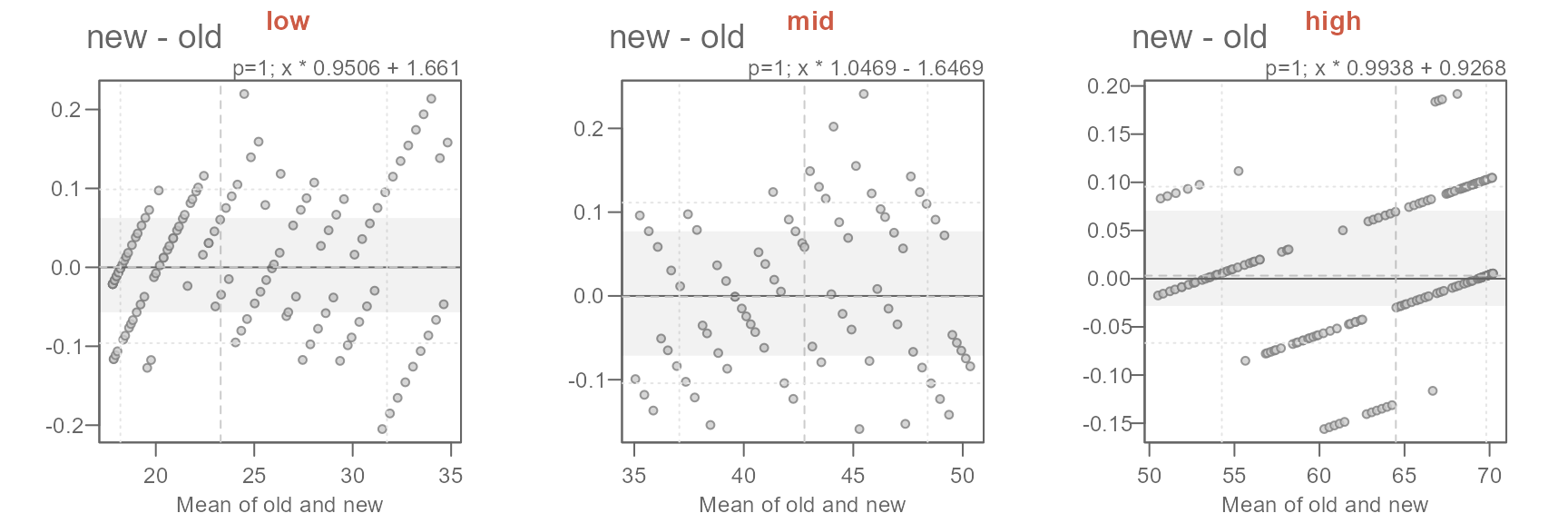

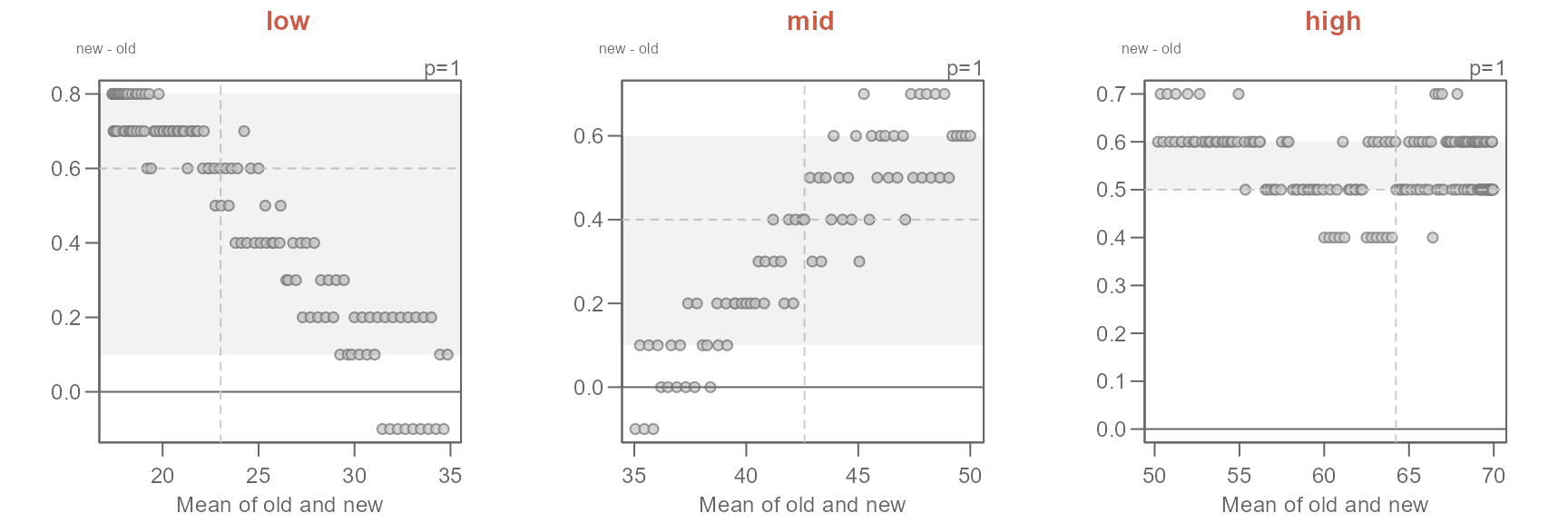

Next, we’ll adopt the suggested offsets generated in the console.

xform <- c("x * 0.9506 + 1.661",

"x * 1.0469 - 1.6469",

"x * 0.9938 + 0.9268")

names(xform) <- labs

sapply(labs, FUN = \(x) {eda_qq(out2[[x]]$old, out2[[x]]$new,

fx = xform[x],

xlab = "old", ylab = "new", md = T)

title(x, line = 3, col.main = "coral3")}

)

The proposed offsets seem to do a good job in characterizing the differences in temperatures.

The characterization of the differences in normal temperatures between the old and new set of normals can be formalized as follows:

\[ new = \begin{cases} old * 0.9506 + 1.661, & T_{avg} < 35 \\ old * 1.0469 - 1.6469, & 35 \le T_{avg} < 50 \\ old * 0.9938 + 0.9268, & T_{avg} \ge 50 \end{cases} \]

The key takeaways from this analysis can be summarized as follows:

- Overall, the new normals are about 0.5°F warmer.

- The offset is not uniform across the full range of temperature values.

- For lower temperature (those less than 35°F), the new normals have a slightly narrower distribution and are about 1.7°F warmer.

- For the mid temperature values (between 35°F and 50°F) the new normals have a slightly wider distribution and are overall about 1.6°F cooler.

- For the higher range of temperature values (those greater than 50°F), the new normals have a slightly narrower distribution and are about 0.9°F warmer.